Aid

In international relations, aid (also known as international aid, overseas aid, foreign aid, economic aid or foreign assistance) is – from the perspective of governments – a voluntary transfer of resources from one country to another. The type of aid given may be classified according to various factors, including its intended purpose, the terms or conditions (if any) under which it is given, its source, and its level of urgency. For example, aid may be classified based on urgency into emergency aid and development aid.

Emergency aid is rapid assistance given to a people in immediate distress by individuals, organizations, or governments to relieve suffering, during and after man-made emergencies (like wars) and natural disasters. Development aid is aid given to support development in general which can be economic development or social development in developing countries. It is distinguished from humanitarian aid as being aimed at alleviating poverty in the long term, rather than alleviating suffering in the short term.

Aid may serve one or more functions: it may be given as a signal of diplomatic approval, or to strengthen a military ally, to reward a government for behavior desired by the donor, to extend the donor's cultural influence, to provide infrastructure needed by the donor for resource extraction from the recipient country, or to gain other kinds of commercial access. Countries may provide aid for further diplomatic reasons. Humanitarian and altruistic purposes are often reasons for foreign assistance.[a]

Aid may be given by individuals, private organizations, or governments. Standards delimiting exactly the types of transfers considered "aid" vary from country to country. For example, the United States government discontinued the reporting of military aid as part of its foreign aid figures in 1958.[b] The most widely used measure of aid is "Official Development Assistance" (ODA).[1]

Definitions and purpose[edit]

The Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development defines its aid measure, Official Development Assistance (ODA), as follows: "ODA consists of flows to developing countries and multilateral institutions provided by official agencies, including state and local governments, or by their executive agencies, each transaction of which meets the following test: a) it is administered with the promotion of the economic development and welfare of developing countries as its main objective, and b) it is concessional in character and contains a grant element of at least 25% (calculated at a rate of discount of 10%)."[2][3] Foreign aid has increased since the 1950s and 1960s (Isse 129).[definition needed] The notion that foreign aid increases economic performance and generates economic growth is based on Chenery and Strout's Dual Gap Model (Isse 129). Chenerya and Strout (1966) claimed that foreign aid promotes development by adding to domestic savings as well as to foreign exchange availability, this helping to close either the savings-investment gap or the export-import gap. (Isse 129).

Carol Lancaster defines foreign aid as "a voluntary transfer of public resources, from a government to another independent government, to an NGO, or to an international organization (such as the World Bank or the UN Development Program) with at least a 25 percent grant element, one goal of which is to better the human condition in the country receiving the aid."[c]

Types[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

The type of aid given may be classified according to various factors, including its level of urgency and intended purpose, or the terms or conditions (if any) under which it is given.

Aid from various sources can reach recipients through bilateral or multilateral delivery systems. Bilateral refers to government to government transfers. Multilateral institutions, such as the World Bank or UNICEF, pool aid from one or more sources and disperse it among many recipients.

By urgency and intended purpose[edit]

Aid may be also classified based on urgency into emergency aid and development aid. Emergency aid is rapid assistance given to a people in immediate distress by individuals, organizations, or governments to relieve suffering, during and after man-made emergencies (like wars) and natural disasters. The term often carries an international connotation, but this is not always the case. It is often distinguished from development aid by being focused on relieving suffering caused by natural disaster or conflict, rather than removing the root causes of poverty or vulnerability. Development aid is aid given to support development in general which can be economic development or social development in developing countries. It is distinguished from humanitarian aid as being aimed at alleviating poverty in the long term, rather than alleviating suffering in the short term.

Official aid may be classified by types according to its intended purpose. Military aid is material or logistical assistance given to strengthen the military capabilities of an ally country.[4]

Humanitarian aid and emergency aid[edit]

Humanitarian aid is material or logistical assistance provided for humanitarian purposes, typically in response to humanitarian crises such as a natural disaster or a man-made disaster.[5]

The provision of emergency humanitarian aid consists of the provision of vital services (such as food aid to prevent starvation) by aid agencies, and the provision of funding or in-kind services (like logistics or transport), usually through aid agencies or the government of the affected country. Humanitarian aid is distinguished from humanitarian intervention, which involves armed forces protecting civilians from violent oppression or genocide by state-supported actors.

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is mandated to coordinate the international humanitarian response to a natural disaster or complex emergency acting on the basis of the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 46/182.[6] The Geneva Conventions give a mandate to the International Committee of the Red Cross and other impartial humanitarian organizations to provide assistance and protection of civilians during times of war. The ICRC, has been given a special role by the Geneva Conventions with respect to the visiting and monitoring of prisoners of war.

Development aid[edit]

Development aid is given by governments through individual countries' international aid agencies and through multilateral institutions such as the World Bank, and by individuals through development charities. For donor nations, development aid also has strategic value;[7] improved living conditions can positively effects global security and economic growth. Official Development Assistance (ODA) is a commonly used measure of developmental aid.

Technical assistance is a sub-type of development aid. It is aid involving highly educated or trained personnel, such as doctors, who are moved into a developing country to assist with a program of development. It can be both programme and project aid.

By terms or conditions of receipt[edit]

Aid can also be classified according to the terms agreed upon by the donor and receiving countries. In this classification, aid can be a gift, a grant, a low or no interest loan, or a combination of these. The terms of foreign aid are oftentimes influenced by the motives of the giver: a sign of diplomatic approval, to reward a government for behaviour desired by the donor, to extend the donor's cultural influence, to enhance infrastructure needed by the donor for the extraction of resources from the recipient country, or to gain other kinds of commercial access.[a]

Other types[edit]

Aid given is generally intended for use by a specific end. From this perspective it may be called:

- Project aid: Aid given for a specific purpose; e.g. building materials for a new school.

- Programme aid: Aid given for a specific sector; e.g. funding of the education sector of a country.

- Budget support: A form of Programme Aid that is directly channelled into the financial system of the recipient country.

- Sector-wide Approaches (SWAPs): A combination of Project aid and Programme aid/Budget Support; e.g. support for the education sector in a country will include both funding of education projects (like school buildings) and provide funds to maintain them (like school books).

- Food aid: Food is given to countries in urgent need of food supplies, especially if they have just experienced a natural disaster. Food aid can be provided by importing food from the donor, buying food locally, or providing cash.

- Faith-based foreign aid: aid that originates in institutions of a religious nature (some examples are, Salvation Army, Catholic Relief Services)

- Private giving: International aid in the form of gifts by individuals or businesses are generally administered by charities or philanthropic organizations who batch them and then channel these to the recipient country.

Scale[edit]

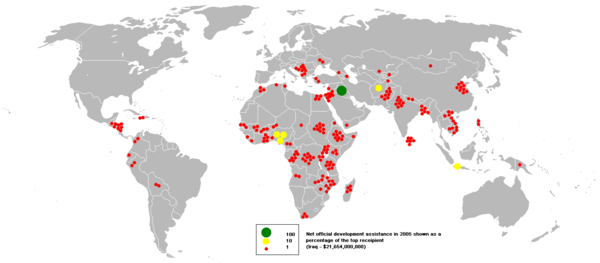

Most official development assistance (ODA) comes from the 30 members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC),[8] or about $150 billion in 2018.[9] For the same year, the OECD estimated that six to seven billion dollars of ODA-like aid was given by ten other states, including China and India.[10]

Top 10 aid recipient countries (2009–2018)[edit]

| Country | US dollars (billions) |

|---|---|

| 51.8 | |

| 44.4 | |

| 37.9 | |

| 32.0 | |

| 28.7 | |

| 27.5 | |

| 27.4 | |

| 25.2 | |

| 24.1 |

Top 10 aid donor countries (2020)[edit]

Official development assistance (in absolute terms) contributed by the top 10 DAC countries is as follows. European Union countries together gave $75,838,040,000 and EU Institutions gave a further $19.4 billion.[12][13] The European Union accumulated a higher portion of GDP as a form of foreign aid than any other economic union.[14]

European Union – $75.8 billion

European Union – $75.8 billion United States – $34.6 billion

United States – $34.6 billion Germany – $23.8 billion

Germany – $23.8 billion United Kingdom – $19.4 billion

United Kingdom – $19.4 billion Japan – $15.5 billion

Japan – $15.5 billion France – $12.2 billion

France – $12.2 billion Sweden – $5.4 billion

Sweden – $5.4 billion Netherlands – $5.3 billion

Netherlands – $5.3 billion Italy – $4.9 billion

Italy – $4.9 billion Canada – $4.7 billion

Canada – $4.7 billion Norway – $4.3 billion

Norway – $4.3 billion

Official development assistance as a percentage of gross national income contributed by the top 10 DAC countries is as follows. Five countries met the longstanding UN target for an ODA/GNI ratio of 0.7% in 2013:[12]

Norway – 1.07%

Norway – 1.07% Sweden – 1.02%

Sweden – 1.02% Luxembourg – 1.00%

Luxembourg – 1.00% Denmark – 0.85%

Denmark – 0.85% United Kingdom – 0.72%

United Kingdom – 0.72% Netherlands – 0.67%

Netherlands – 0.67% Finland – 0.55%

Finland – 0.55% Switzerland – 0.47%

Switzerland – 0.47% Belgium – 0.45%

Belgium – 0.45% Ireland – 0.45%

Ireland – 0.45%

European Union countries that are members of the Development Assistance Committee gave 0.42% of GNI (excluding the $15.93 billion given by EU Institutions).[12]

Quantifying aid[edit]

Official development assistance[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

Official development assistance (ODA) is a term coined by the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to measure aid. ODA refers to aid from national governments for promoting economic development and welfare in low and middle income countries.[15] ODA can be bilateral or multilateral. This aid is given as either grants, where no repayment is required, or as concessional loans, where interest rates are lower than market rates.[d]

Loan repayments to multilateral institutions are pooled and redistributed as new loans. Additionally, debt relief, partial or total cancellation of loan repayments, is often added to total aid numbers even though it is not an actual transfer of funds. It is compiled by the Development Assistance Committee. The United Nations, the World Bank, and many scholars use the DAC's ODA figure as their main aid figure because it is easily available and reasonably consistently calculated over time and between countries.[d][16] The DAC classifies aid in three categories:

- Official Development Assistance (ODA): Development aid provided to developing countries (on the "Part I" list) and international organizations with the clear aim of economic development.[17]

- Official Aid (OD): Development aid provided to developed countries (on the "Part II" list).

- Other Official Flows (OOF): Aid which does not fall into the other two categories, either because it is not aimed at development, or it consists of more than 75% loan (rather than grant).

Aid is often pledged at one point in time, but disbursements (financial transfers) might not arrive until later.

In 2009, South Korea became the first major recipient of ODA from the OECD to turn into a major donor. The country now provides over $1 billion in aid annually.[18]

Not included as international aid[edit]

Most monetary flows between nations are not counted as aid. These include market-based flows such as foreign direct investments and portfolio investments, remittances from migrant workers to their families in their home countries, and military aid. In 2009, aid in the form of remittances by migrant workers in the United States to their international families was twice as large as that country's humanitarian aid.[19] The World Bank reported that, worldwide, foreign workers sent $328 billion from richer to poorer countries in 2008, over twice as much as official aid flows from OECD members.[19] The United States does not count military aid in its foreign aid figures.[20]

Improving aid effectiveness[edit]

Aid effectiveness is the degree of success or failure of international aid (development aid or humanitarian aid). Concern with aid effectiveness might be at a high level of generality (whether aid on average fulfils the main functions that aid is supposed to have), or it might be more detailed (considering relative degrees of success between different types of aid in differing circumstances).

Questions of aid effectiveness have been highly contested by academics, commentators and practitioners: there is a large literature on the subject. Econometric studies in the late 20th century often found the average effectiveness of aid to be minimal or even negative. Such studies have appeared on the whole to yield more affirmative results in the early 21st century, but the picture is complex and far from clear in many respects.

Many prescriptions have been made about how to improve aid effectiveness. In 2003–2011 there existed a global movement in the name of aid effectiveness, around four high level forums on aid effectiveness. These elaborated a set of good practices concerning aid administration co-ordination and relations between donors and recipient countries. The Paris Declaration and other results of these forums embodied a broad consensus on what needed to be done to produce better development results.[21] From 2011 this movement was subsumed in one concerned more broadly with effective development co-operation, largely embodied by the Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation.Criticism[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2021) |

Statistical studies have produced widely differing assessments of the correlation between aid and economic growth: there is little consensus with some studies finding a positive correlation[22] while others find either no correlation or a negative correlation.[23] One consistent finding is that project aid tends to cluster in richer parts of countries, meaning most aid is not given to poor countries or poor recipients.[24] In the case of Africa, Asante (1985) gives the following assessment:

Summing up the experience of African countries both at the national and at the regional levels it is no exaggeration to suggest that, on balance, foreign assistance, especially foreign capitalism, has been somewhat deleterious to African development. It must be admitted, however, that the pattern of development is complex and the effect upon it of foreign assistance is still not clearly determined. But the limited evidence available suggests that the forms in which foreign resources have been extended to Africa over the past twenty-five years, insofar as they are concerned with economic development, are, to a great extent, counterproductive.[e]

Peter Singer argues that over the last three decades, "aid has added around one percentage point to the annual growth rate of the bottom billion." He argues that this has made the difference between "stagnation and severe cumulative decline."[25] Aid can make progress towards reducing poverty worldwide, or at least help prevent cumulative decline. Despite the intense criticism on aid, there are some promising numbers. In 1990, approximately 43 percent of the world's population was living on less than $1.25 a day and has dropped to about 16 percent in 2008. Maternal deaths have dropped from 543,000 in 1990 to 287,000 in 2010. Under-five mortality rates have also dropped, from 12 million in 1990 to 6.9 million in 2011.[26] Although these numbers alone sound promising, there is a gray overcast: many of these numbers actually are falling short of the Millennium Development Goals. There are only a few goals that have already been met or projected to be met by the 2015 deadline.

The economist William Easterly and others have argued that aid can often distort incentives in poor countries in various harmful ways. Aid can also involve inflows of money to poor countries that have some similarities to inflows of money from natural resources that provoke the resource curse.[27][28] This is partially because aid given in the form of foreign currency causes exchange rate to become less competitive and this impedes the growth of manufacturing sector which is more conducive in the cheap labour conditions. Aid also can take the pressure off and delay the painful changes required in the economy to shift from agriculture to manufacturing.[29]

Some believe that aid is offset by other economic programs such as agricultural subsidies. Mark Malloch Brown, former head of the United Nations Development Program, estimated that farm subsidies cost poor countries about US$50 billion a year in lost agricultural exports:

It is the extraordinary distortion of global trade, where the West spends $360 billion a year on protecting its agriculture with a network of subsidies and tariffs that costs developing countries about US$50 billion in potential lost agricultural exports. Fifty billion dollars is the equivalent of today's level of development assistance.[30][31]

Some have argued that the major international aid organizations have formed an aid cartel.[32]

In response to aid critics, a movement to reform U.S. foreign aid has started to gain momentum. In the United States, leaders of this movement include the Center for Global Development, Oxfam America, the Brookings Institution, InterAction, and Bread for the World. The various organizations have united to call for a new Foreign Assistance Act, a national development strategy, and a new cabinet-level department for development.[33]

In November 2012, a spoof charity music video was produced by a South African rapper named Breezy V. The video "Africa for Norway" promoting "Radi-Aid" was a parody of Western charity initiatives like Band Aid which, he felt, exclusively encouraged small donations to starving children, creating a stereotypically negative view of the continent.[34] Aid in his opinion should be about funding initiatives and projects with emotional motivation as well as money. The parody video shows Africans getting together to campaign for Norwegian people suffering from frostbite by supplying them with unwanted radiators.[34]

Anthropologist and researcher Jason Hickel concludes from a 2016 report[35] by the US-based Global Financial Integrity (GFI) and the Centre for Applied Research at the Norwegian School of Economics that

the usual development narrative has it backwards. Aid is effectively flowing in reverse. Rich countries aren't developing poor countries; poor countries are developing rich ones... The aid narrative begins to seem a bit naïve when we take these reverse flows into account. It becomes clear that aid does little but mask the maldistribution of resources around the world. It makes the takers seem like givers, granting them a kind of moral high ground while preventing those of us who care about global poverty from understanding how the system really works.[36]

Unintended consequences[edit]

Some of the unintended effects include labor and production disincentives, changes in recipients' food consumption patterns and natural resources use patterns, distortion of social safety nets, distortion of NGO operational activities, price changes, and trade displacement. These issues arise from targeting inefficacy and poor timing of aid programs. Food aid can harm producers by driving down prices of local products, whereas the producers are not themselves beneficiaries of food aid. Unintentional harm occurs when food aid arrives or is purchased at the wrong time, when food aid distribution is not well-targeted to food-insecure households, and when the local market is relatively poorly integrated with broader national, regional and global markets. The use of food aid for emergencies can reduce the unintended consequences, although it can contribute to other associated with the use of food as a weapon or prolonging or intensifying the duration of civil conflicts. Also, aid attached to institution building and democratization can often result in the consolidation of autocratic governments when effective monitoring is absent.[37]

Increasing conflict duration[edit]

International aid organizations identify theft by armed forces on the ground as a primary unintended consequence through which food aid and other types of humanitarian aid promote conflict. Food aid usually has to be transported across large geographic territories and during the transportation it becomes a target for armed forces, especially in countries where the ruling government has limited control outside of the capital. Accounts from Somalia in the early 1990s indicate that between 20 and 80 percent of all food aid was stolen, looted, or confiscated.[38] In the former Yugoslavia, the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) lost up to 30 percent of the total value of aid to Serbian armed forces. On top of that 30 percent, bribes were given to Croatian forces to pass their roadblocks in order to reach Bosnia.[39]

The value of the stolen or lost provisions can exceed the value of the food aid alone since convoy vehicles and telecommunication equipment are also stolen. MSF Holland, international aid organization operating in Chad and Darfur, underscored the strategic importance of these goods, stating that these "vehicles and communications equipment have a value beyond their monetary worth for armed actors, increasing their capacity to wage war"[39]

A famous instance of humanitarian aid unintentionally helping rebel groups occurred during the Nigeria-Biafra civil war in the late 1960s,[40] where the rebel leader Odumegwu Ojukwu only allowed aid to enter the region of Biafra if it was shipped on his planes. These shipments of humanitarian aid helped the rebel leader to circumvent the siege on Biafra placed by the Nigerian government. These stolen shipments of humanitarian aid caused the Biafran civil war to last years longer than it would have without the aid, claim experts.[39]

The most well-known instances of aid being seized by local warlords in recent years come from Somalia, where food aid is funneled to the Shabab, a Somali militant group that controls much of Southern Somalia. Moreover, reports reveal that Somali contractors for aid agencies have formed a cartel and act as important power brokers, arming opposition groups with the profits made from the stolen aid"[41]

Rwandan government appropriation of food aid in the early 1990s was so problematic that aid shipments were canceled multiple times.[42] In Zimbabwe in 2003, Human Rights Watch documented examples of residents being forced to display ZANU-PF Party membership cards before being given government food aid.[43] In eastern Zaire, leaders of the Hema ethnic group allowed the arrival of international aid organizations only upon agreement not give aid to the Lendu (opposition of Hema). Humanitarian aid workers have acknowledged the threat of stolen aid and have developed strategies for minimizing the amount of theft en route. However, aid can fuel conflict even if successfully delivered to the intended population as the recipient populations often include members of rebel groups or militia groups, or aid is "taxed" by such groups.

Academic research emphatically demonstrates that on average food aid promotes civil conflict. Namely, increase in US food aid leads to an increase in the incidence of armed civil conflict in the recipient country.[38] Another correlation demonstrated is food aid prolonging existing conflicts, specifically among countries with a recent history of civil conflict. However, this does not find an effect on conflict in countries without a recent history of civil conflict.[38] Moreover, different types of international aid other than food which is easily stolen during its delivery, namely technical assistance and cash transfers, can have different effects on civil conflict.

Community-driven development (CDD) programs have become one of the most popular tools for delivering development aid. In 2012, the World Bank supported 400 CDD programs in 94 countries, valued at US$30 billion.[44] Academic research scrutinizes the effect of community-driven development programs on civil conflict.[45] The Philippines' flagship development program KALAHI-CIDSS is concluded to have led to an increase in violent conflict in the country. After the program's start, some municipalities experienced and statistically significant and large increase in casualties, as compared to other municipalities who were not part of the CDD. Casualties suffered by government forces as a result of insurgent-initiated attacks increased significantly.

These results are consistent with other examples of humanitarian aid exacerbating civil conflict.[45] One explanation is that insurgents attempt to sabotage CDD programs for political reasons – successful implementation of a government-supported project could weaken the insurgents' position. Related findings[46] of Beath, Christia, and Enikolopov further demonstrate that a successful community-driven development program increased support for the government in Afghanistan by exacerbating conflict in the short term, revealing an unintended consequence of the aid.

Dependency and other economic effects[edit]

One of the economic cases against aid transfers, in the form of food or other resources, is that it discourages recipients from working, everything else held constant.[47] This claim undermines the support for transfers, as heated debates over the past decade about domestic welfare programs in Europe and North America show. Targeting errors of inclusion are said to magnify the labor market disincentive effects inherent to food aid (or any other form of transfer) by providing benefits to those who are most able and willing to turn transfers into leisure instead of increased food consumption.

Labor distortion can arise when Food-For-Work (FFW) Programs are more attractive than work on recipients' own farms/businesses, either because the FFW pays immediately, or because the household considers the payoffs to the FFW project to be higher than the returns to labor on its own plots. Food aid programs hence take productive inputs away from local private production, creating a distortion due to substitution effects, rather than income effects.[47]

Beyond labor disincentive effects, food aid can have the unintended consequence of discouraging household-level production. Poor timing of aid and FFW wages that are above market rates cause negative dependency by diverting labor from local private uses, particularly if FFW obligations decrease labor on a household's own enterprises during a critical part of the production cycle. This type of disincentive impacts not only food aid recipients but also producers who sell to areas receiving food aid flows.[48][49][50][51][52]

FFW programs are often used to counter a perceived dependency syndrome associated with freely distributed food.[47] However, poorly designed FFW programs may cause more risk of harming local production than the benefits of free food distribution. In structurally weak economies, FFW program design is not as simple as determining the appropriate wage rate. Empirical evidence[53] from rural Ethiopia shows that higher-income households had excess labor and thus lower (not higher as expected) value of time, and therefore allocated this labor to FFW schemes in which poorer households could not afford to participate due to labor scarcity. Similarly, FFW programs in Cambodia have shown to be an additional, not alternative, source of employment and that the very poor rarely participate due to labor constraints.[54]

Furthermore, food aid can drive down local or national food prices in at least three ways.

- First, monetization of food aid can flood the market, increasing supply. In order to be granted the right to monetize, operational agencies must demonstrate that the recipient country has adequate storage facilities and that the monetized commodity will not result in a substantial disincentive in either domestic agriculture or domestic marketing.[55]

- Second, households receiving aid may decrease demand for the commodity received or for locally produced substitutes or, if they produce substitutes or the commodity received, they may sell more of it. This can be most easily understood by dividing a population in a food aid recipient area into subpopulations based on two criteria: whether or not they receive food aid (recipients vs. non-recipients) and whether they are net sellers or net buyers of food. Because the price they receive for their output is lower, however, net sellers are unambiguously worse off if they do not receive food aid or some other form of compensatory transfer.[47]

- Finally, recipients may sell food aid to purchase other necessities or complements, driving down prices of the food aid commodity and its substitutes, but also increasing demand for complements. Most recipient economies are not robust and food aid inflows can cause large price decreases, decreasing producer profits, limiting producers' abilities to pay off debts and thereby diminishing both capacity and incentives to invest in improving agricultural productivity. However, food aid distributed directly or through FFW programs to households in northern Kenya during the lean season can foster increased purchase of agricultural inputs such as improved seeds, fertilizer and hired labor, thereby increasing agricultural productivity.[54][56]

Corruption[edit]

A 2020 article published in Studies in Comparative International Development analyzed contract-level data over the period 1998 through 2008 in more than a hundred recipient countries. As a risk indicator for corruption, the study used the prevalence of single bids submitted in "high-risk" competitive tenders for procurement contracts funded by World Bank development aid.[57] ("High-risk" tenders are those with a higher degree of World Bank oversight and control; as a result, the study authors noted that "our findings are not representative of all aid spending financed by the World Bank, but only that part where risks are higher" and more stringent oversight thus deemed necessary.[57]) The study authors found "that donor efforts to control corruption in aid spending through national procurement systems, by tightening oversight and increasing market openness, were effective in reducing corruption risks."[57] The study also found that countries with high party system institutionalization (PSI) and countries with greater state capacity had lower prevalence of single bidding, lending support for "theories of corruption control based on reducing opportunities and increasing constraints on the power of public administrators."[57]

A 2018 study published in the Journal of Public Economics investigated with Chinese aid projects in Africa increased local-level corruption. Matching Afrobarometer data (on perceptions of corruption) to georeferenced data on Chinese development finance project sites, the study found that active Chinese project sites had more widespread local corruption. The study found that the apparent increase in corruption did not appear to be driven by increased economic activity, but rather could be linked to a negative Chinese impact on norms (e.g., the legitimization of corruption).[58] The study noted that: "Chinese aid stands out from World Bank aid in this respect. In particular, whereas the results indicate that Chinese aid projects fuel local corruption but have no observable impact on short term local economic activity, they suggest that World Bank aid projects stimulate local economic activity without any consistent evidence of it fuelling local corruption."[58]

Changed consumption patterns[edit]

Food aid that is relatively inappropriate to local uses can distort consumption patterns.

Food aid is usually exported from temperate climate zones and is often different than the staple crops grown in recipient countries, which usually have a tropical climate. The logic of food export inherently entails some effort to change consumers' preferences, to introduce recipients to new foods and thereby stimulate demand for foods with which recipients were previously unfamiliar or which otherwise represent only a small portion of their diet.[47]

Massive shipments of wheat and rice into the West African Sahel during the food crises of the mid-1970s and mid-1980s were widely believed to stimulate a shift in consumer demand from indigenous coarse grains – millet and sorghum – to western crops such as wheat. During the 2000 drought in northern Kenya, the price of changaa (a locally distilled alcohol) fell significantly and consumption seems to have increased as a result. This was a result of grain food aid inflows increasing the availability of low-cost inputs to the informal distilling industry.[59]

Natural resource overexploitation[edit]

Recent research suggests that patterns of food aid distribution may inadvertently affect the natural environment, by changing consumption patterns and by inducing locational change in grazing and other activities. A pair of studies in Northern Kenya found that food aid distribution seems to induce greater spatial concentration of livestock around distribution points, causing localized rangeland degradation, and that food aid provided as whole grain requires more cooking, and thus more fuelwood, stimulating local deforestation.[60][61]

The welfare impacts of any food aid-induced changes in food prices are decidedly mixed, underscoring the reality that it is impossible to generate only positive intended effects from an international aid program.

Death of local industries[edit]

Foreign aid kills local industries in developing countries.[62] Foreign aid in the form of food aid that is given to poor countries or underdeveloped countries is responsible for the death of local farm industries in poor countries.[62] Local farmers end up going out of business because they cannot compete with the abundance of cheap imported aid food, that is brought into poor countries as a response to humanitarian crisis and natural disasters.[63] Large inflows of money that come into developing countries, from the developed world, in a foreign aid, increases the price of locally produced goods and products.[64] Due to their high prices, export of local goods reduces.[64] As a result, local industries and producers are forced to go out of business.

Ulterior agendas[edit]

Aid is seldom given from motives of pure altruism; for instance it is often given as a means of supporting an ally in international politics. It may also be given with the intention of influencing the political process in the receiving nation. Whether one considers such aid helpful may depend on whether one agrees with the agenda being pursued by the donor nation in a particular case. During the conflict between communism and capitalism in the twentieth century, the champions of those ideologies – the Soviet Union and the United States – each used aid to influence the internal politics of other nations, and to support their weaker allies. Perhaps the most notable example was the Marshall Plan by which the United States, largely successfully, sought to pull European nations toward capitalism and away from communism. Aid to underdeveloped countries has sometimes been criticized as being more in the interest of the donor than the recipient, or even a form of neocolonialism.[65]

S.K.B'. Asante lists some specific motives a donor may have for giving aid: defence support, market expansion, foreign investment, missionary enterprise, cultural extension.[f] In recent decades, aid by organizations such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank has been criticized as being primarily a tool used to open new areas up to global capitalists, and being only secondarily, if at all, concerned with the wellbeing of the people in the recipient countries.

Vaccine diplomacy[edit]

Beyond aid[edit]

As a result of these numerous criticisms, other proposals for supporting developing economies and poverty stricken societies. Some analysts, such as researchers at the Overseas Development Institute, argue that current support for the developing world suffers from a policy incoherence and that while some policies are designed to support the third world, other domestic policies undermine its impact,[73] examples include:

- encouraging developing economies to develop their agriculture with a focus on exports is not effective on a global market where key players, such as the US and EU, heavily subsidise their products

- providing aid to developing economies' health sectors and the training of personnel is undermined by migration policies in developed countries that encourage the migration of skilled health professionals

One measure of this policy incoherence is the Commitment to Development Index (CDI) published by the Center for Global Development. The index measures and evaluates 22 of the world's richest countries on policies that affect developing countries, in addition to simply aid. It shows that development policy is more than just aid; it also takes into account trade, investment, migration, environment, security, and technology.

Thus, some states are beginning to go Beyond Aid and instead seek to ensure there is a policy coherence, for example see Common Agricultural Policy reform or Doha Development Round. This approach might see the nature of aid change from loans, debt cancellation, budget support etc., to supporting developing countries. This requires a strong political will, however, the results could potentially make aid far more effective and efficient.[73]

History[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2022) |

An early example of the military type of aid is the First Crusade, which began when Byzantine Greek emperor Alexios I Komnenos asked for help in defending Byzantium, the Holy Land, and the Christians living there from the Seljuk takeover of the region. The call for aid was answered by Pope Urban II, when, at the Council of Piacenza of 1095, he called for Christendom to rally in military support of the Byzantines with references to the "Greek Empire and the need of aid for it."[74]

After World War II the Marshall Plan (and similar programs for Asia, and the Point Four program for Latin America) became the major American aid program, and became a model for its foreign aid policies for decades.[75] The U.S. gave away about $20 billion in Marshall Plan grants and other grants and low-interest long-term loans to Western Europe, 1945 to 1951. Economic historians Bradford De Long and Barry Eichengreen conclude it was, "History's Most Successful Structural Adjustment Program." They state:

- It was not large enough to have significantly accelerated recovery by financing investment, aiding the reconstruction of damaged infrastructure, or easing commodity bottlenecks. We argue, however, that the Marshall Plan did play a major role in setting the stage for post-World War II Western Europe's rapid growth. The conditions attached to Marshall Plan aid pushed European political economy in a direction that left its post World War II "mixed economies" with more "market" and less "controls" in the mix.[76]

For much of the period since World War II to the present "foreign aid was used for four main purposes: diplomatic [including military/security and political interests abroad], developmental, humanitarian relief and commercial."[77]: 13

Arab countries as "New Donors"[edit]

The mid-1970s saw some new emerging donors in the face of the world crises, discovery of oil, the impending Cold War. While in many literature they are popularly called the 'new donors', they are by no means new. In the sense, that the former USSR had been contributing to the popular Aswan Dam in Egypt as early as 1950s or India and other Asian countries were known for their assistance under the Colombo Plan [78] Of these the Arab countries in particularly have been quite influential. Kuwait, Saudi Arabi and United Arab Emirates are the top donors in this sense. The aid from Arab countries are often less documented for the fact that they do not follow the standard aid definitions of the OECD and DAC countries. Many times, the aid from Arab countries are made by private funds[79] owned by the families of the monarch. Many Arab recipient countries have also avoided of speaking on aid openly in order to digress from the idea of hierarchy of Eurocentrism and Wester-centrism, which are in some ways reminders of the colonial pasts.[80] Hence, the classification of such transfers are tricky.[81]

Over and on top of this, there has been extensive research that Arab aid is often allocated initially to Arab countries, and perhaps recently to some sub-Saharan African countries which have shown Afro-Arab unity. This is especially true considering the fact that aid by Arab donors is more geographically concentrated, given without conditionality and often to poorest nations in the Middle East and North Africa.[82] This is perhaps potentially due to the existence of Arab Fund for Technical Assistance to African and Arab Countries (AFTAAAC) or the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa (BADEA).[83] OECD data for example also shows Arab countries donate more to lower middle income countries, contrast to the DAC donors. It is not completely clear why such a bias must exists, but some studies have studied the sectoral donations.[84]

Another big difference between the traditional DAC (Western) donors and the Arab donors is that Arab donors give aid unconditionally. Typically they have followed a rule of non-interference in the policy of the recipient. The Arab approach is limited to giving advice on policy matters when they discover clear failures. This kind of view is often repeated in many studies.[85] These kind of approach has always been problematic for the relationship Arab countries have with institutions like IMF, World Bank etc., since Arab countries are members of these institutions and in some ways they oppose the conditionality guidelines for granting aid and conditions on repayment agreed internationally.[86] More recently, UAE has been declaring its aid flows with the IMF and OECD.[87] Data from this reveals that potential opacity in declaring aid may also result from the fact some Arab countries do not want to be seen openly as supporters of a cause or a proxy group in a neighboring country or region. The exact impact of such bilateral aid is difficult to discern.

Arab aid has often been used a tool for steering foreign policy. The 1990 Iraq invasion of Kuwait triggered an increase of Arab aid and large amounts went to countries which supported Kuwait. Many countries around this time still kept supporting Iraq, despite rallying against the war. This lead the Kuwait national assembly to decide to deny aid to supporters of Iraq. Saudi Arabia for example did a similar thing, In 1991, after the war, countries against Iraq –Egypt, Turkey and Morocco became the three major aid recipients of Saudi aid.[88]Several similar stances have arisen in the recent years after the Arab Spring of 2011 particularly.

Public attitudes[edit]

Academic research has suggested that members of the public overestimate how much their governments spend on aid. There is significant opposition to spending on aid but experiments have demonstrated that providing people with more information about correct levels of spending reduces this opposition.[89]

See also[edit]

- Aid agency

- Debt relief

- International Aid Transparency Initiative

- Transparency International

- White savior

- Effective altruism

Nations:

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Lancaster, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Lancaster, p. 67: "In 1957 the administration (with congressional support) separated economic from military assistance and created a Development Loan Fund (DLF) to provide concessional credits to developing countries world-wide (i.e. not, as in the past, just those in areas of potential conflict with Moscow) to promote their long-term growth."

- ^ Carol Lancaster. Foreign Aid. 2007. p.9.

- ^ a b Lancaster uses either ODA or ODA plus OA ("Official Assistance" – another DAC government-aid category) as her main statistic. She considers it better to add the OA but very often just uses the ODA figure alone; e.g., for Table 1.1 (p. 13), Table 2.2 (p. 39) and Table 2.3 (p. 43). In any case the difference is now moot since the DAC recently merged the two categories.

- ^ Asante, p. 265

- ^ Asante, p. 251.

References[edit]

- ^ "Official development assistance – definition and coverage - OECD". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ "DAC Glossary of Key Terms and Concepts". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ "The DAC in Dates, 2006 Edition. Section, "1972"" (PDF). www.oecd.org. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ Securing tyrants or fostering reform?: U.S. internal security assistance to repressive and transitioning regimes. Jones, Seth G., 1972-, International Security and Defense Policy Center., Open Society Institute. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corp. 2006. ISBN 9780833042620. OCLC 184843895.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Defining humanitarian assistance". Development Initiatives. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ "A/RES/46/182 - E". www.un.org. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ "10 Accomplishments of U.S. Foreign Aid - BORGEN". BORGEN. 9 October 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ "DAC members - OECD". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ "Development aid drops in 2018, especially to neediest countries". OECD. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ "Other official providers not reporting to the OECD". OECD. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ "Net official development assistance and official aid received (current US$) - Data". data.worldbank.org.

- ^ a b c "Official Development Assistance: Council approves the Annual Report to the European Council on EU Development Aid Targets". www.consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ "EU". Donor Tracker. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ Hunt, Michael (2014). The World Transformed 1945 to the Present. New York: New York. pp. 516–517. ISBN 9780199371020.

- ^ "Official Development Assistance (ODA) - OECD". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ "Net official development assistance and official aid received (current US$) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ "Official development assistance – definition and coverage". OECD. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ^ "Giving Foreign Aid Helps Korea - The Asia Foundation". asiafoundation.org. 30 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Migration and development: The aid workers who really help". economist. 8 October 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ "How Does the U.S. Spend Its Foreign Aid?". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ "Effective development co-operation - OECD". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- ^ Juselius, Katarina; Møller, Niels Framroze; Tarp, Finn (7 January 2013). "The Long-Run Impact of Foreign Aid in 36 African Countries: Insights from Multivariate Time Series Analysis*" (PDF). Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. 76 (2): 153–184. doi:10.1111/obes.12012. hdl:10.1111/obes.12012. ISSN 0305-9049. S2CID 53685791.

- ^ Dreher, Axel; Eichenauer, Vera; Gehring, Kai; Langlotz, Sarah; Lohmann, Steffen (18 October 2015). "Does foreign aid affect growth?". VoxEU.org. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Briggs, Ryan (2017). "Does Foreign Aid Target the Poorest?". International Organization. 71 (1): 187–206. doi:10.1017/S0020818316000345. S2CID 157749892.

- ^ Singer, Peter. 2009. The Life You Can Save. New York:Random House.

- ^ Provost, Claire (31 October 2012). "Millennium Development Goals – The Key Datasets You Need to Know". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 22 January 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ Collier, Paul (September 2006). "Is Aid Oil? An Analysis of Whether Africa Can Absorb More Aid". World Development. 34 (9): 1482–1497. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.01.002. ISSN 0305-750X.

- ^ Djankov, Simeon; Montalvo, Jose G.; Reynal-Querol, Marta (1 September 2008). "The curse of aid". Journal of Economic Growth. 13 (3): 169–194. doi:10.1007/s10887-008-9032-8. ISSN 1381-4338. S2CID 195315143.

- ^ "The Bottom Billion". Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ "Mark Malloch Brown at Makerere University in Uganda". 12 November 2002. Archived from the original on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Kristof, Nicholas D. (5 July 2002). "Farm Subsidies That Kill". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Easterly, William (2002). "The cartel of good intentions: The problem of bureaucracy in foreign aid". Journal of Economic Policy Reform. 5 (131): 40–49. doi:10.2307/3183416. ISSN 0015-7228. JSTOR 3183416.

- ^ "Coalition seeks cabinet-level foreign aid". POLITICO. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Africa: Why Are Africans for Norway?". AllAfrica.com. Africa. 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ "New Report on Unrecorded Capital Flight Finds Developing Countries are Net-Creditors to the Rest of the World". GFIntegrity.org. 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ Hickel, Jason (14 January 2017). "Aid in Reverse: How Poor Countries Develop Rich Countries". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ Nieto, Camilo; Schenoni, Luis (24 December 2018). "Backing Despots?" (PDF). Democracy and Security. 14 (1): 153–184. doi:10.1111/obes.12012. hdl:10.1111/obes.12012. ISSN 0305-9049. S2CID 53685791.

- ^ a b c Nunn, Nathan, and Nancy Qian. "US Food Aid and Civil Conflict". American Economic Review, vol. 104, no. 6, 2014, pp. 1630–1666., doi:10.1257/aer.104.6.1630.

- ^ a b c Polman, Linda (14 September 2010). The Crisis Caravan: What's Wrong with Humanitarian Aid?. Henry Holt and Company. pp. 96–104. ISBN 9781429955768.

- ^ Barnett, Michael (3 March 2011). Empire of Humanity: A History of Humanitarianism. Cornell University Press. pp. 133–147. ISBN 978-0801461095.

- ^ "Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia pursuant to Security Council resolution 1853 (2008) (S/2010/91)". United Nations Security Council. 10 March 2010. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Uvin, Peter (1998). Aiding Violence: The Development Enterprise in Rwanda. Kumarian Press. p. 90. ISBN 9781565490833.

- ^ Thurow, Roger, and Scott Kilman. 2009. Enough: Why the World's Poorest Starve in an Age of Plenty. New York: PublicAffairs. (pp.206)

- ^ Susan, Wong (1 March 2012). What have been the impacts of World Bank Community-Driven Development Programs? CDD impact evaluation review and operational and research implications (Report). pp. 1–93.

- ^ a b Crost, Benjamin; Felter, Joseph; Johnston, Patrick (June 2014). "Aid Under Fire: Development Projects and Civil Conflict". American Economic Review. 104 (6): 1833–1856. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.269.7048. doi:10.1257/aer.104.6.1833. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ^ Beath, Andrew; Christia, Fotini; Enikolopov, Ruben (1 July 2012). Winning hearts and minds through development ? evidence from a field experiment in Afghanistan (Report). pp. 1–33.

- ^ a b c d e Barrett, Christopher B. (1 March 2006). Food Aid's Intended and Unintended Consequences (PDF) (Report). Rochester, NY. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1142286. S2CID 19628562. SSRN 1142286.

- ^ Jackson, Tony; Eade, Deborah (1982). Against the grain: the dilemma of project food aid. OXFAM. ISBN 9780855980634.

- ^ Richardson, Laurie; International, Grassroots (1997). Feeding dependency, starving democracy: USAID policies in Haiti. Grassroots International.

- ^ Lappé, Frances Moore; Collins, Joseph; Fowler, Cary (1979). Food First: Beyond the Myth of Scarcity. Ballantine Books. ISBN 9780345251503.

- ^ Molla, Md Gyasuddin (1990). Politics of food aid: case of Bangladesh. Academic Publishers.

- ^ Salisbury, L.N. (1992). Enhancing Development Sustainability and Eliminating Food Aid Dependency: Lessons from the World Food Programme. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University.

- ^ Barrett, Christopher B.; Clay, Daniel C. (1 June 2003). "Self-Targeting Accuracy in the Presence of Imperfect Factor Markets: Evidence from Food-for-Work in Ethiopia". Journal of Development Studies. 39 (5): 152–180. doi:10.1080/00220380412331333189. S2CID 216142208. SSRN 1847703.

- ^ a b Barrett, Christopher B. (January 2001). "Does Food Aid Stabilize Food Availability?" (PDF). Economic Development and Cultural Change. 49 (2): 335–349. doi:10.1086/452505. hdl:1813/57993. ISSN 0013-0079. S2CID 224787897.

- ^ Ralyea, B.; Food Aid Management Monetization Working Group (1999). P.L. 480 Title II Cooperating Sponsor Monetization Manual.

- ^ Bezuneh, Mesfin; Deaton, Brady J.; Norton, George W. (1 February 1988). "Food Aid Impacts in Rural Kenya" (PDF). American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 70 (1): 181–191. doi:10.2307/1241988. ISSN 0002-9092. JSTOR 1241988.

- ^ a b c d Dávid-Barrett, Elizabeth; Fazekas, Mihály; Hellmann, Olli; Márk, Lili; McCorley, Ciara (2020). "Controlling Corruption in Development Aid: New Evidence from Contract-Level Data". Studies in Comparative International Development. 55 (4): 481–515. doi:10.1007/s12116-020-09315-4.

- ^ a b Ann-Sofie Isaksson & Andreas Kotsadam, Chinese aid and local corruption, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 159, March 2018, pp. 146-159.

- ^ Barrett, Christopher Brendan; Maxwell, Daniel G. (2005). Food Aid After Fifty Years: Recasting Its Role. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415701259.

- ^ McPeak J.G. (2003a) Analyzing and assessing localized degradation of the commons. Land Economics, 78(4): 515-536.

- ^ McPeak, John G. (May 2003). Fuelwood Gathering and Use in Northern Kenya: Implications for Food Aid and Local Environments. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bandow, Doug. "Foreign Aid, Or Foreign Hindrance". Forbes. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ NW, 1310 L. Street; Washington, 7th Floor (16 August 2007). "Foreign Aid Kills". Competitive Enterprise Institute. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Why Foreign Aid Is Hurting Africa" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ Asante, S.K.B. (1985). "International Assistance and international Capitalism: Supportive or Counterproductive?". In Carter, Gwendolen Margaret; O'Meara, Patrick (eds.). African Independence: The First Twenty-Five Years. Indiana University Press. pp. 249-274. ISBN 0253302552. OCLC 11211907. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Srinivas, Krishna Ravi (11 March 2021). "Understanding Vaccine Diplomacy for the Anthropocene, Anti-Science Age". The Wire Science. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ Snyder, Alison (20 August 2020). "A coronavirus vaccine is a chance for China to show its scientific muscle". Axios. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ Deng, Chao (17 August 2020). "China Seeks to Use Access to Covid-19 Vaccines for Diplomacy". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ Abduazimov, Muzaffar S. (2021). "Inside Diplomacy during the Pandemic: Change in the Means and Ways of Practice". Indonesian Quarterly. SSRN 3854295.

- ^ Blume, Stuart (19 March 2020). McInnes, Colin; Lee, Kelley; Youde, Jeremy (eds.). "The Politics of Global Vaccination Policies". The Oxford Handbook of Global Health Politics. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190456818.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-045681-8. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ Jennings, Michael (22 February 2021). "Vaccine diplomacy: how some countries are using COVID to enhance their soft power". The Conversation. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ Hotez, Peter J. (26 June 2014). ""Vaccine Diplomacy": Historical Perspectives and Future Directions". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (6): e2808. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002808. ISSN 1935-2727. PMC 4072536. PMID 24968231.

- ^ a b "'Beyond Aid' for sustainable development". ODI. April 2009. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ "D.C. Munro, The American Historical Review, Volume 27, Issue 4". www.academic.oup.com. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ Raymond H. Geselbracht (2015). Foreign Aid and the Legacy of Harry S. Truman. Truman State UP. pp. 17–20. ISBN 9781612481234.

- ^ DeLong, J. Bradford; Eichengreen, Barry (1993). "The Marshall Plan: History's Most Successful Structural Adjustment Program". In Dornbusch, Rudiger; Nolling, Wilhelm; Layard, Richard (eds.). Postwar Economic Reconstruction and Lessons for the East Today. MIT Press. pp. 189–230. ISBN 978-0-262-04136-2.

- ^ Lancaster, Carol (2008). Foreign aid: diplomacy, development, domestic politics (Repr. ed.). Chicago, Ill.: Univ. of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-47045-0.

- ^ "Will 'Emerging Donors' Change the Face of International Co-operation?".

- ^ DARPE (24 November 2021). "Top 6 Arab Donor Organizations -". Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ Challand, Benoit (2014). "Revisiting Aid in the Arab Middle East". Mediterranean Politics. 19 (3): 281–298. doi:10.1080/13629395.2014.966983.

- ^ Kibria, Ahsan; Oladi, Reza (2021). "Political Economy of Aid Allocation: The Case of Arab Donors". The World Economy. 44 (8): 2460–2495. doi:10.1111/twec.13139.

- ^ Shushan, Debra (2011). "The Rise (and Decline?) of Arab Aid: Generosity and Allocation in the Oil Era". World Development. 39 (11): 1969–1980. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.07.025.

- ^ Neumayer, Eric (2003). "What factors determine the allocation of aid by Arab countries and multilateral agencies?". The Journal of Development Studies. 39 (4): 134–147. doi:10.1080/713869429.

- ^ Neumayer, Eric (2004). "Arab-related Bilateral and Multilateral Sources of Development Finance: Issues, Trends, and the Way Forward". The World Economy. 27 (2): 281–300. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9701.2004.00600.x. hdl:10419/53012.

- ^ van den Boogaerde, Pierre. "The Composition and Distribution of Financial Assistance from Arab Countries and Arab Regional Institutions". International Monetary Fund. SSRN 884923.

- ^ Villanger, Espen (2007). "Arab Foreign Aid: Disbursement Patterns, Aid Policies and Motives". CMI Report R 2007: 2. R 2007: 2.

- ^ Cochrane, Logan (2021). "The United Arab Emirates as a global donor: what a decade of foreign aid data transparency reveals". Development Studies Research. 8: 49–62. doi:10.1080/21665095.2021.1883453.

- ^ van den Boogaerde, Pierre (15 June 1991). "Financial Assistance from Arab Countries and Arab Regional Institutions". IMF Occasional Papers. ISBN 978-1-55775-180-5.

- ^ Scotto, Thomas J.; Reifler, Jason; Hudson, David; vanHeerde-Hudson, Jennifer (2017). "We Spend How Much? Misperceptions, Innumeracy, and Support for the Foreign Aid in the United States and Great Britain" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Political Science. 4 (2): 119–128. doi:10.1017/XPS.2017.6. ISSN 2052-2630. S2CID 53989821.

Sources[edit]

- Malmqvist, Håkan (February 2000). "Development Aid, Humanitarian Assistance and Emergency Relief". Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Sweden. Archived from the original on 25 November 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

- Rogerson, Andrew; Hewitt, Adrian; Waldenberg, David (2004). The International Aid System 2005 - 2010: Forces for and Against Change. Overseas Development Institute. ISBN 9780850037081.

- Easterly, William (2006). The White Man's Burden: Why the West's Effort to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-59420-037-3.

- Shah, Anup (28 September 2014). "Foreign Aid for Development Assistance – Global Issues". www.globalissues.org. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "Millions Saved". millionssaved.cgdev.org. Retrieved 28 May 2018. A compilation of case studies of successful foreign assistance by the Center for Global Development.

- "Real Aid: An Agenda for Making Aid Work" (PDF). ActionAid. 1 May 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 June 2005. Retrieved 28 May 2018. – analysis of the proportion of aid wasted on consultants, tied aid, etc.

- Mousseau, Frederic; Mittal, Anuradha. "Food Sovereignty: Ending World Hunger in Our Time". The Humanist. 2006: 35–40.

- Lancaster, Carol; Ann Van Dusen (2005). Organizing Foreign Aid: Confronting the Challenges of the 21st Century. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0-8157-5113-7.

- Ali, Abdiweli M.; Said Isse, Hodan (2007). "Foreign Aid and Free Trade and their Effect on Income: A Panel Analysis". The Journal of Developing Areas. 41 (1): 127–142. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.614.3911. doi:10.1353/jda.2008.0016. S2CID 154393943.

External links[edit]

- Foreign Relations and International Aid resources from University of Colorado–Boulder

- International Aid and Development at Curlie

- AidData – a web portal for information on development aid, including a database of aid activities financed by donors worldwide

- EuropeAid Cooperation Office

- OECD Development Co-operation Directorate (DAC)

- Overseas Development Institute Archived 6 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Aid Reform Campaign Archived 23 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine at Oxfam America

- Does Foreign Aid Work? Efforts to Evaluate U.S. Foreign Assistance Congressional Research Service

- Foreign Aid at Brookings Institution

- Center for Global Development's Modernizing U.S. Foreign Assistance Initiative

- Aid Workers Network

- www.realityofaid.org

- Aid Harmonization: What Will It Take to Meet the Millennium Development Goals?

- Aid at GlobalIssues.org

- Euforic makes information on Europe's development cooperation more accessible

- The Development Executive Group Resource for staffing, tracking, winning, and implementing development projects.

- European Network on Debt and Development reports, news and links on development aid.

- How Food Aid Work.

- Aid Guide Archived 11 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine at OneWorld.net

- NL-Aid Archived 7 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Advance Integral Development

- Foreign Aid Projects 1955–2010

- International Aid at Islamic Help