Oasis (band)

Oasis | |

|---|---|

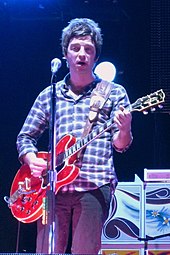

Lead singer Liam Gallagher and songwriter and lead guitarist Noel Gallagher performing in 2005 | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Manchester, England |

| Genres | |

| Discography | |

| Years active |

|

| Labels | |

| Spinoffs | |

| Members | |

| Past members | |

| Website | oasisinet |

Oasis are an English rock band formed in Manchester in 1991. The group initially consisted of Liam Gallagher (lead vocals), Paul "Bonehead" Arthurs (guitar), Paul "Guigsy" McGuigan (bass guitar) and Tony McCarroll (drums), with Liam asking his older brother Noel Gallagher (lead guitar, vocals) to join as a fifth member a few months later to finalise their formation. Noel became the de facto leader of the group and took over the songwriting duties for the band's first four albums. They are characterised as one of the defining and most globally successful groups of the Britpop genre.[1]

Oasis signed to independent record label Creation Records in 1993 and released their record-setting debut album Definitely Maybe (1994), which topped the UK Albums Chart and quickly became the fastest-selling debut album in British history at the time. The following year they released follow up album (What's the Story) Morning Glory? (1995) with new drummer Alan White in the midst of a highly publicised chart rivalry with peers Blur. Spending ten weeks at number one on the British charts, (What's the Story) Morning Glory? was also an international chart success and became one of the best-selling albums of all time, the fifth-best-selling album in the UK and the best-selling album in the UK of the 1990s. The Gallagher brothers featured regularly in tabloid newspapers throughout the 1990s for their public disputes and wild lifestyles. In 1996, Oasis performed two nights at Knebworth for an audience of 125,000 each time, the largest outdoor concerts in UK history at the time. In 1997, Oasis released their highly anticipated third studio album, Be Here Now, which became the fastest-selling album in UK chart history but retrospectively was seen as a critical disappointment.

Founding members Arthurs and McGuigan left in 1999 during the recording of the band's fourth studio album Standing on the Shoulder of Giants (2000). They were replaced by former Heavy Stereo guitarist Gem Archer on guitar and former Ride guitarist Andy Bell on bass guitar. White departed in 2004, replaced by guest drummer Zak Starkey, and later by Chris Sharrock. Oasis released three more studio albums in the 2000s: Heathen Chemistry (2002), Don't Believe the Truth (2005) and Dig Out Your Soul (2008). The group abruptly disbanded in 2009 after the sudden departure of Noel Gallagher. The remaining members of the band continued under the name Beady Eye until their disbandment in 2014. Both Gallagher brothers have had successful solo careers. In 2024, Oasis announced that they would reform in 2025 for performances around the world as part of the Oasis Live '25 Tour.

As of 2024, Oasis have sold over 75 million records worldwide,[2] making them one of the best-selling music artists of all time.[3][4] They are among the most successful acts in the history of the UK Singles Chart and the UK Albums Chart, with eight UK number-one singles and eight UK number-one albums.[5][6][7] The band also achieved three Platinum albums in the US. They won 17 NME Awards, nine Q Awards, four MTV Europe Music Awards and six Brit Awards, including one in 2007 for Outstanding Contribution to Music and one for the "Best Album of the Last 30 Years" for (What's the Story) Morning Glory?. They were also nominated for two Grammy Awards.[8]

History

[edit]1991–1993: Formation and early years

[edit]In 1991, bassist Paul McGuigan, guitarist Paul Arthurs, drummer Tony McCarroll, and singer Chris Hutton formed a band called the Rain. Unsatisfied with Hutton, Arthurs invited and auditioned acquaintance Liam Gallagher as a potential replacement. Liam suggested that the band name be changed to Oasis, inspired by an Inspiral Carpets tour poster in the childhood bedroom he shared with his brother Noel, which listed the Oasis Leisure Centre in Swindon as a venue.[9] Oasis played their first gig on 14 August 1991 at the Boardwalk club in Manchester, bottom of the bill below the Catchmen and Sweet Jesus.[10][11] Noel, who was working as a roadie for Inspiral Carpets, went with them to watch Liam's band play, and he was impressed with what he heard.[12]

Noel approached the group about joining on the provision that he would become the band's sole songwriter and leader, and that they would commit to an earnest pursuit of commercial success. Arthurs recalled, "He had loads of stuff written. When he walked in, we were a band making a racket with four tunes. All of a sudden, there were loads of ideas."[13] Under Noel, the band crafted a musical approach that relied on simplicity, with Arthurs and McGuigan restricted to playing barre chords and root bass notes, McCarroll playing basic rhythms, and the band's amplifiers turned up to create distortion. Oasis thus created a sound described as being "so devoid of finesse and complexity that it came out sounding pretty much unstoppable".[14]

1993–1995: Breakthrough with Definitely Maybe

[edit]After over a year of live shows, rehearsals and a recording of a demo, the Live Demonstration tape, in May 1993, Oasis were spotted by the Creation Records co-owner Alan McGee. Oasis were invited to play a gig at King Tut's Wah Wah Hut club in Glasgow by Sister Lovers, who shared their rehearsal rooms. Oasis, along with a group of friends, hired a van and made the journey to Glasgow. When they arrived, they were refused entry as they were not on that night's set list. They and McGee have given contradicting statements about how they entered the club.[15] They were given the opening slot and impressed McGee, who was there to see 18 Wheeler, and Sister Lovers, whose member Debbie Turner was a close friend of McGee's from his days frequenting the Haçienda in Manchester.[16] McGee offered them a recording contract; however, they did not sign until several months later.[17] Due to problems securing an American contract, Oasis signed a worldwide contract with Sony, which in turn licensed Oasis to Creation in the UK.[18]

Following a limited white label release of the demo of their song "Columbia", Oasis went on a UK tour to promote the release of their first single, "Supersonic", playing venues such as the Tunbridge Wells Forum, a converted public toilet. "Supersonic" was released in April 1994, reaching number 31 in the charts.[19] The release was followed by "Shakermaker", which became the subject of a plagiarism suit, with Oasis paying $500,000 in damages.[20] Their third single, "Live Forever", was their first to enter the top ten of the UK Singles Chart. After troubled recording and mixing sessions, Oasis's debut album, Definitely Maybe, was released on 29 August 1994. It entered the UK Albums Chart at number one within a week of its release, and at the time becoming the fastest selling debut album in the UK.[21]

Nearly a year of constant live performances and recordings, along with a hedonistic lifestyle, damaged the band. This behaviour culminated during a gig in Los Angeles in September 1994, leading to an inept performance by Liam during which he made offensive remarks about American audiences and hit Noel with a tambourine.[22] Upset, Noel temporarily quit the band and flew to San Francisco (it was from this incident the song "Talk Tonight" was written). He was tracked down by Creation's Tim Abbot and they made a trip to Las Vegas. Once there, he was persuaded to continue with the band. He reconciled with Liam and the tour resumed in Minneapolis.[23] The group followed up with the fourth single from Definitely Maybe, "Cigarettes & Alcohol", and the Christmas single "Whatever", issued in December 1994, which entered the British charts at number three.[24]

1995–1996: (What's the Story) Morning Glory?, international success, and peak popularity

[edit]In April 1995, "Some Might Say" became their first number-one UK single. At the same time, McCarroll was ousted from the band. He said he was "unlawfully expelled from the partnership" for what he called a "personality clash" with the brothers. The Gallaghers were critical of McCarroll's musical ability, with Noel saying: "I like Tony as a geezer but he wouldn't have been able to drum the new songs."[25][26] He was replaced by Alan White, formerly of Starclub and the brother of the percussionist Steve White, who was recommended to Noel by Paul Weller. White made his debut with Oasis on a Top of the Pops performance of "Some Might Say".[27]

Oasis began recording material for their second album that May in Rockfield Studios near Monmouth.[27] During this period, the British press seized upon a supposed rivalry between Oasis and another Britpop band, Blur. Previously, Oasis had not associated with the Britpop movement and were not invited to perform on the BBC's Britpop Now programme introduced by Blur's singer, Damon Albarn. On 14 August 1995, Blur and Oasis released singles on the same day, setting up the "Battle of Britpop" that dominated the national news.[28] Blur's "Country House" outsold Oasis's "Roll with It" 274,000 copies to 216,000 during the week.[29] Oasis's management argued that "Country House" had sold more because it was less expensive (£1.99 vs £3.99) and because there were two versions of the "Country House" single, with different B-sides, forcing fans to buy two copies.[30] Creation said there were problems with the barcode on the "Roll with It" single case, which did not record all sales.[31] Noel Gallagher told The Observer in September that he hoped members of Blur would "catch AIDS and die", which caused a media furore.[32] He apologised in a formal letter to various publications.[33]

McGuigan briefly left Oasis in September 1995, citing nervous exhaustion. He was replaced by Scott McLeod, formerly of the Ya Ya's, who was featured on some of the tour dates as well as in the "Wonderwall" video before leaving abruptly while on tour in the US. McLeod contacted Noel, saying he felt he had made the wrong decision. Noel replied: "I think you have, too. Good luck signing on."[34]

Although a softer sound initially led to mixed reviews, Oasis's second album, (What's the Story) Morning Glory?, was a worldwide commercial success, selling over four million copies and becoming the fifth-best-selling album in UK chart history.[35] By 2008, it had sold up to 22 million copies globally, making it one of the best-selling albums of all time.[36] The album produced two more singles, "Wonderwall" and "Don't Look Back in Anger", which reached numbers two and one. It also contained "Champagne Supernova", which featured guitar and backing vocals by Paul Weller and received critical acclaim. The song reached number one on the US Modern Rock Tracks chart. In November 1995, Oasis played on back-to-back nights at Earls Court in London, the biggest ever indoor gigs in Europe at the time. Noel played a customised Sheraton guitar emblazoned with a Union Jack, commercially released by Epiphone as the "Supernova".[37]

On 27 and 28 April 1996, Oasis played their first headline outdoor concerts, at Maine Road football stadium, home of Manchester City F.C., of whom the Gallagher brothers had been fans since childhood.[38] Highlights from the second night featured on the video ...There and Then, released later the same year (along with footage from their Earls Court gigs). As their career reached its zenith, Oasis performed to 80,000 people over two nights at Balloch Country Park at Loch Lomond in Scotland on 3 and 4 August, before back-to-back concerts at Knebworth House on 10 and 11 August. The band sold out both shows within minutes. The audience of 125,000 people each night (2.5 million people applied for tickets, and 250,000 were actually sold, meaning the possibility of 20 sold out nights) was a record-breaking number for an outdoor concert held in the UK and remains the largest demand for a show in British history.[39][40]

"What Oasis has done in Britain, unifying an entire country under the banner of a single pop act, a band could no longer achieve in a country like the US. In Britain the band reigns unchallenged as the most popular act since the Beatles, there is an Oasis CD in roughly one of every three homes there. Last month, the band drew 250,000 people to Knebworth for the biggest outdoor concerts in the country's history. The group's battling brothers, Liam and Noel Gallagher, appear as regularly as royalty on tabloid covers."

— Neil Strauss, September 1996, writing in The New York Times on the group's escalating popularity[41]

Oasis were due to record an episode of MTV Unplugged at the Royal Festival Hall but Liam pulled out, citing a sore throat. He watched the performance from a balcony with beer and cigarettes, heckling Noel's singing between songs.[42] Four days later the group left for a tour of American arenas but Liam refused to go; the band decided to continue the tour with Noel on vocals.[43] Liam rejoined the tour on 30 August and on 4 September 1996, Oasis performed "Champagne Supernova" at the 1996 MTV Video Music Awards at Radio City Music Hall in New York City.[44] Liam made gestures at Noel during his guitar solo, then spat beer all over the stage before storming off.[44] A few weeks later Noel flew home without the band, who followed on another flight.[45] This event prompted media speculation that the group were splitting up. The brothers soon reconciled and decided to complete the tour.[46]

1996–1999: Be Here Now and The Masterplan

[edit]Oasis spent the end of 1996 and the first quarter of 1997 at Abbey Road Studios in London and Ridge Farm Studios in Surrey recording their third album. Quarrels between the Gallagher brothers plagued the recording sessions. Be Here Now was released in August 1997. Preceded by the UK number one single "D'You Know What I Mean?", the album was their most anticipated effort, and as such became the subject of considerable media attention. Footage of excited fans clutching copies made ITV News at Ten, leading anchorman Trevor McDonald to intone the band's phrase "mad for it".[47] By the end of the first day of release, Be Here Now had sold 424,000 units and first week sales reached 696,000, making it the fastest-selling album in British history until Adele released 25 in 2015.[47][48] The album debuted at number two on the Billboard 200 in the US, but its first week sales of 152,000—below expected sales of 400,000 copies—were considered a disappointment.[49] Predominantly written by Noel Gallagher during a holiday with Kate Moss, Johnny Depp and Mick Jagger, Gallagher has since expressed regret over the writing process of Be Here Now, adding it doesn't match up to the standard of the band's first two albums;

In the studio it was great, and on the day it came out it was great. It was only when I got on tour that I was thinking, "It doesn't fucking stand up." ... People are prepared to have stand-up rows with me in the street: "I fucking love that album!" And I'm like, "Mate, look, I wrote the fucking thing. I know how much effort I put into it. It wasn't that much."[50]

"For a little while, Be Here Now demanded superlatives. Its path was paved with five-star reviews, like petals thrown beneath a Roman emperor's feet. No album in history has experienced such a swift and dramatic reversal of fortune. Be Here Now was reframed first as a disappointment and then as a disaster. It burned out quickly, falling well short of the sales achieved by 1995's (What's the Story) Morning Glory?, with many copies ending up in secondhand racks. Noel himself quickly disowned it, dismissing it in the 2003 Britpop documentary Live Forever as "the sound of five men in the studio, on coke, not giving a fuck".

— Dorian Lynskey writing in The Guardian, October 2016[47]

Noel had been ambivalent about the album in pre-release interviews, telling NME, "This record ain't going to surprise many people." However, there was nobody around him to echo his reservations. "Everyone's going: 'It's brilliant!'" he later said. "And right towards the end, we're doing the mixing and I'm thinking to myself: 'Hmmm, I don't know about this now.'"[47] When the album was released Oasis were woven into Britain's cultural fabric like no other band since the Beatles, and according to their former press officer Johnny Hopkins: "There were more hangers-on, constantly telling them they were the greatest thing. That tended to block out the critical voices."[47] Dorian Lynskey writes, "If it couldn't be Britpop's zenith, then it must be the nadir. It can't be just a collection of songs – some good, some bad, most too long, all insanely overproduced – but an emblem of the hubris before the fall, like a dictator's statue pulled to the ground by a vengeful mob."[47]

After the conclusion of the Be Here Now Tour in early 1998, amidst much media criticism, the group kept a low profile. Later in the year, Oasis released a compilation album of fourteen B-sides, The Masterplan. "The really interesting stuff from around that period is the B-sides. There's a lot more inspired music on the B-sides than there is on Be Here Now itself, I think," said Noel in an interview in 2008.[51]

1999–2001: Line-up change and Standing on the Shoulder of Giants

[edit]In early 1999, the band began work on their fourth studio album. First details were announced in February, with Mark Stent revealed to be taking a co-producing role. Things were not going well and the shock departure of founding member Paul "Bonehead" Arthurs was announced in August. This departure was reported at the time as amicable, with Noel stating Arthurs wanted to spend more time with his family. Arthurs' statement clarified his leaving as "to concentrate on other things".[52] However, Noel has since offered a contradicting version: that a series of violations of Noel's "no drink or drugs" policy (imposed by Noel so that Liam could sing properly) for the album's sessions resulted in a confrontation between the two.[53] Two weeks later the departure of bassist Paul McGuigan was announced. The Gallagher brothers held a press conference shortly thereafter, in which they assured reporters that "the future of Oasis is secure. The story and the glory will go on."[54]

After the completion of the recording sessions, the band began searching for replacement members. The first new member to be announced was new lead/rhythm guitarist Colin "Gem" Archer, formerly of Heavy Stereo, who later claimed to have been approached by Noel Gallagher only a couple of days after Arthurs' departure was publicly announced.[55] Finding a replacement bassist took more time and effort: the band were rehearsing with David Potts, but he quickly resigned, and they brought in Andy Bell, former guitarist/songwriter of Ride and Hurricane #1 as their new bassist. Bell had never played bass before and had to learn to play it (with Noel since saying, "I was amazed that Andy was up for actually playing the bass y'know, cos he's such a good guitarist"), along with a handful of songs from Oasis's back catalogue, in preparation for a scheduled US tour in December 1999.[56]

With the folding of Creation Records, Oasis formed their own label, Big Brother, which released all of Oasis's subsequent records in the UK and Ireland. Oasis's fourth album, Standing on the Shoulder of Giants, was released in February 2000 to good first-week sales. It reached number one on the British charts and peaked at number 24 on the Billboard charts.[57][58] Four singles were released from the album: "Go Let It Out", "Who Feels Love?", "Sunday Morning Call" and "Where Did It All Go Wrong?", of which the first three were top five UK singles.[59] The "Go Let It Out" music video was shot before Bell joined the group and therefore featured the unusual line-up of Liam on rhythm guitar, Archer on lead guitar and Noel on bass. With the departure of the founding members, the band made several small changes to their image and sound. The cover featured a new "Oasis" logo, designed by Gem Archer, and the album was also the first Oasis release to include a song written by Liam Gallagher, entitled "Little James". The songs also had more experimental, psychedelic influences.[60] Standing on the Shoulder of Giants received lukewarm reviews[60] and sales slumped in its second week of release in the US.[61]

To support the record the band staged an eventful world tour. While touring in Barcelona in 2000, Oasis were forced to cancel a gig when an attack of tendinitis caused Alan White's arm to seize up, and the band spent the night drinking instead. After a row between the two brothers, Noel declared he was quitting touring overseas altogether, and Oasis were supposed to finish the tour without him.[62] Noel eventually returned for the Irish and British legs of the tour, which included two major shows at Wembley Stadium. A live album of the first show, called Familiar to Millions, was released in late 2000 to mixed reviews.[63]

2001–2003: Heathen Chemistry

[edit]

Throughout 2001, Oasis split time between sessions for their fifth studio album and live shows around the world. Gigs included the month-long Tour of Brotherly Love with the Black Crowes and Spacehog and a show in Paris supporting Neil Young. The album, Heathen Chemistry, Oasis's first album with new members Andy Bell and Gem Archer, was released in July 2002. The album reached number 1 in the UK and number 23 in the US,[64][65] although critics gave it mixed reviews.[66][67] There were four singles released from the album: "The Hindu Times", "Stop Crying Your Heart Out", "Little by Little/She Is Love" which were written by Noel, and "Songbird", written by Liam and the first single not to be written by Noel. The record blended the band's sonic experiments from their last albums, but also went for a more basic rock sound.[66] The recording of Heathen Chemistry was much more balanced for the band, with all of the members, apart from White, writing songs. Johnny Marr provided additional guitar as well as backup vocals on a couple of songs.

After the album's release, the band embarked on a successful world tour that was once again filled with incidents. In August 2002, while the band were on tour in the US, Noel, Bell and touring keyboardist Jay Darlington were involved in a car accident in Indianapolis. While none of the band members sustained any major injuries, some shows were cancelled as a result. In December 2002, the latter half of the German leg of the band's European tour had to be postponed after Liam Gallagher, Alan White and three other members of the band's entourage were arrested after a violent brawl at a Munich nightclub. The band had been drinking heavily and tests showed that Liam had used cocaine.[68] Liam lost two front teeth and kicked a police officer in the ribs, while Alan suffered minor head injuries after getting hit with an ashtray.[69] Two years later Liam was fined around £40,000.[70] The band finished their tour in March 2003 after returning to those postponed dates.

2003–2007: Alan White's departure and Don't Believe the Truth

[edit]Oasis began recording a sixth album in late December 2003 with producers Death in Vegas at Sawmills Studios in Cornwall.[71][72] The album was originally planned for a September 2004 release, to coincide with the 10th anniversary of the release of Definitely Maybe, However, long-time drummer Alan White, who at this time had played on nearly all of the band's material, had been asked to leave the band.[73][74] At the time, his brother Steve White stated on his own website that "the spirit of being in a band was kicked out of him" and he wanted to be with his girlfriend.[75] White was replaced by Zak Starkey, the Who's drummer and the son of the Beatles' drummer, Ringo Starr. Though Starkey performed on studio recordings and toured with the band, he was not officially a member and the band were a four-piece for the first time in their career. Starkey played publicly for the first time at Poole Lighthouse.

A few days later, Oasis, with Starkey, headlined the Glastonbury Festival for the second time in their career and performed a largely greatest hits set, which included two new songs — Gem Archer's "A Bell Will Ring" and Liam Gallagher's "The Meaning of Soul". The performance received negative reviews, with NME calling it a "disaster".[76] The BBC's Tom Bishop called Oasis's set "lacklustre and uneventful ... prompting a mixed reception from fans", mainly because of Liam's uninspired singing and Starkey's lack of experience with the band's material.[77]

After much turbulence, the band's sixth album was finally recorded in Los Angeles-based Capitol Studios from October to December the same year. Producer Dave Sardy took over the lead producing role from Noel,[78] who decided to step back from these duties after a decade of producing leadership over the band. In May 2005, after three years and as many scrapped recording sessions, the band released their sixth studio album, Don't Believe the Truth, fulfilling their contract with Sony BMG. It followed the path of Heathen Chemistry as being a collaborative project again, rather than a Noel-written album.[79] The album was the first in a decade not to feature drumming by Alan White, marking the recording debut of Starkey. The record was generally hailed as the band's best effort since Morning Glory by fans and critics alike, spawning two UK number one singles: "Lyla" and "The Importance of Being Idle", whilst "Let There Be Love" entered at number 2. Oasis picked up two awards at the Q Awards: one People's Choice Award and the second for Don't Believe the Truth as Best Album.[80] Following in the footsteps of Oasis's previous five albums, Don't Believe the Truth also entered the UK album charts at number one.[81] By 2013 the album had sold more than 6 million copies worldwide.[82]

In May 2005, the band's new line-up embarked on a large scale world tour. Beginning on 10 May 2005 at the London Astoria, and finishing on 31 March 2006 in front of a sold-out gig in Mexico City, Oasis played more live shows than at any time since the Definitely Maybe Tour, visiting 26 countries and headlining 113 shows for over 3.2 million people. The tour passed without any major incidents and was the band's most successful in more than a decade. The tour included sold-out shows at New York's Madison Square Garden and LA's Hollywood Bowl.[83] A rockumentary film made during the tour, entitled Lord Don't Slow Me Down directed by Baillie Walsh was released in October 2007.[84]

Oasis released a compilation double album entitled Stop the Clocks in 2006, featuring what the band considers to be their "definitive" songs.[85] The band received the Brit Award for Outstanding Contribution to Music in February 2007, playing several of their most famous songs afterwards.[86] Oasis released their first ever digital-only release, "Lord Don't Slow Me Down", in October 2007. The song debuted at number ten in the UK singles chart.[87]

2007–2009: Dig Out Your Soul

[edit]The band's resurgence in popularity since the success of Don't Believe the Truth was highlighted in February 2008 when, in a poll to find the fifty greatest British albums of the last fifty years conducted by Q magazine and HMV, two Oasis albums were voted first and second (Definitely Maybe and (What's The Story) Morning Glory? respectively). Two other albums by the band appeared in the list – Don't Believe The Truth came in at number fourteen, and the album that has previously been heavily criticised by some of the media, Be Here Now, made the list at no. 22.[88]

Oasis recorded for a couple of months in 2007 – between July and September – completing work on two new songs and demoing the rest. They then took a two-month break because of the birth of Noel's son. The band re-entered the studio on 5 November 2007 and finished recording around March 2008[89] with producer Dave Sardy.

In May 2008, Zak Starkey left the band after recording Dig Out Your Soul, the band's seventh studio album. He was replaced by former Icicle Works and the La's drummer Chris Sharrock on their tour but Chris was not an official member of the band and Oasis remained as a four-piece. The first single from the record was "The Shock of the Lightning" written by Noel Gallagher, and was pre-released on 29 September 2008. Dig Out Your Soul, the band's seventh studio album, was released on 6 October and went to number one in the UK and number five on the Billboard 200. The band started touring for a projected 18-month-long tour expected to last till September 2009, with support from Kasabian, the Enemy and Twisted Wheel.[90] On 7 September 2008, while performing at Virgin Festival in Toronto, a member of the audience ran on stage and physically assaulted Noel.[91] Noel suffered three broken and dislodged ribs as a result from the attack, and the group had to cancel several shows while he recovered.[91] In June 2008, the band re-signed with Sony BMG for a three-album deal.[92]

On 25 February 2009, Oasis received the NME Award for Best British Band of 2009,[93] as well as Best Blog for Noel's 'Tales from the Middle of Nowhere'.[94] On 4 June 2009, Oasis played the first of three concerts at Manchester's Heaton Park and after having to leave the stage twice due to a generator failure, came on the third time to declare the gig was now a free concert; it delighted the 70,000 ticket holders, 20,000 of whom claimed the refund.[95] The band's two following gigs at the venue, on 6 and 7 June, proved a great success, with fans turning out in the thousands despite the changeable weather and first night's sound issues.[96]

2009–2024: Split and aftermath

[edit]

After Liam contracted laryngitis, Oasis cancelled a gig at V Festival in Chelmsford on 23 August 2009.[97] Noel stated in 2011 that the gig was cancelled due to Liam having "a hangover".[98] Liam subsequently sued Noel, and demanded an apology, stating: "The truth is I had laryngitis, which Noel was made fully aware of that morning, diagnosed by a doctor."[99] Noel issued an apology and the lawsuit was dropped.[100] The band were due to perform on 28 August 2009 at the Rock en Seine festival near Paris, however mid-way through Bloc Party's set at the festival their frontman Kele Okereke (alongside Bloc Party tour manager Peter Hill) announced that Oasis would not be performing.[101][102][103][104] Two hours later, a statement from Noel appeared on the band's website:

It is with some sadness and great relief...I quit Oasis tonight. People will write and say what they like, but I simply could not go on working with Liam a day longer.[105]

Liam and the remaining members of Oasis decided to continue under the name Beady Eye, releasing two studio albums until their break-up in 2014.[106] Liam started a solo career and has released three studio albums, with Arthurs joining him occasionally on tour. Noel formed a solo project, Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds and has released four studio albums, with Sharrock and Archer later joining as members. Bell reunited with former band Ride.[107]

On 16 February 2010, Oasis won Best British Album of the Last 30 Years – for (What's the Story) Morning Glory? – at the 2010 Brit Awards.[108] Liam collected the award alone before presenting his speech, which thanked Bonehead, McGuigan and Alan White but not Noel, and throwing his microphone and the band's award into the crowd;[109] he later defended his actions.[110] Time Flies... 1994–2009, a compilation of singles, was released on 14 June 2010.[111] It became the band's final album to reach number one on the UK Albums Chart.[112] A remastered 3-disc version of Definitely Maybe was released on 19 May 2014.[113]

A documentary titled Oasis: Supersonic was released on 26 October 2016, which tells the story of Oasis from their beginnings to the height of their fame during the summer of 1996.[114] Another concert documentary film was released in September 2021, in celebration of the 25th anniversary of Oasis's two record breaking concerts at Knebworth Park in August 1996.[115] A new demo recording, "Don't Stop...", previously only known from a recording during a soundcheck in Hong Kong, was rediscovered during the COVID-19 pandemic, and was released on 3 May 2020;[116] it passed 1 million views on YouTube that morning and reached number 80 on the UK Singles Chart based on streaming alone.[117]

2024–present: Reunion and Oasis Live '25 Tour

[edit]By early 2023, both Gallagher brothers expressed interest in reuniting the band if it was done on the right terms. On 27 August 2024, almost 15 years to the date of their 2009 split, Oasis announced that they would reform for performances in the UK and Ireland in July and August 2025, stating "The guns have fallen silent. The stars have aligned. The great wait is over. Come see. It will not be televised."[118][119][120] After the announcement of the reunion, it was rumoured that former members Paul "Bonehead" Arthurs, Gem Archer, Andy Bell, Zak Starkey and some members of Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds will perform alongside the two brothers.[121][122][123][124][125] Former drummer Alan White also teased his involvement in the reunion,[126][125] while original drummer Tony McCarroll said he does not think that he will be back.[127] Liam Gallagher also teased on Twitter that new members could join the band on tour.[128]

On 30 August 2024, following the news of the reunion, Oasis released the 30th anniversary edition of their debut album Definitely Maybe. A week later the album charted at number 1 in the UK Official Albums Chart Top 100, 30 years after its release along with Time Flies and Morning Glory which rose to number 3 and 4 in the charts. Three more Oasis albums also entered the top 100 in the charts, The Masterplan at number 41, Be Here Now at number 42 and Heathen Chemistry at number 97.[129] Oasis's single "Live Forever" charted at number 8 in the UK Official Singles Chart Top 40, two places higher than it originally finished in 1994, along with "Don't Look Back In Anger" which reached number 9 and "Wonderwall" which reached number 11.[130]

Although no new album from the band has been confirmed, Liam Gallagher has teased new music on X.[131] On 7 September 2024, he said a new Oasis album is "already finished" and that he has been blown away by the music his brother had written.[132][133]

The band also added American and Australian dates to their touring schedule in 2025.[134][135][136]

Musical style and influences

[edit]Musically, Oasis have been regarded as a rock band.[138][139] More specifically, the band has been described as Britpop,[118][140][141] indie rock,[119][142] alternative rock,[143] pop rock,[144] neo-psychedelia,[145] psychedelic rock,[145] and power pop.[146] Oasis were most heavily influenced by the Beatles, an influence that was frequently labelled as an "obsession" by British media.[147][148][149] The band were also strongly influenced by the other 1960s British Invasion acts,[150] including the Kinks,[151] the Rolling Stones,[152] and the Who.[153] Another major influence, especially during the band's early career, was 1970s British punk rock, in particular the Sex Pistols and their album Never Mind the Bollocks, Here's the Sex Pistols (1977),[137][154] as well as the Damned,[155] and the Jam/Paul Weller.[156] In addition, members of Oasis have cited as an influence or inspiration AC/DC,[157] Acetone,[158] Burt Bacharach,[159] Beck,[158] the Bee Gees,[160] David Bowie,[161] the Doors,[162] Peter Green–era Fleetwood Mac,[163] Grant Lee Buffalo,[158] the La's,[164] MC5,[165] Nirvana,[166] Pink Floyd,[167] Slade,[168] the Smiths,[169] The Soundtrack of Our Lives,[170] the Specials,[163] the Stone Roses,[171] the Stooges,[172] T. Rex,[173] the Verve,[158] the Velvet Underground/Lou Reed,[174][175] and Neil Young.[151]

Oasis albums consistently featured loud tracks characterized by nasal vocals. These dynamic Britpop compositions stood in stark contrast to the more polished pop tunes of Blur, their chart rivals.[176] Especially in their early years, Oasis's musical style and lyrics were grounded in the working-class backgrounds of Liam and Noel. The brothers became known for their rebellious demeanor, self-assured personalities, and sibling rivalry; these characteristics garnered media interest from the band's beginnings and endured throughout their entire career.[177]

Legal battles over songwriter credits

[edit]Legal action has been taken against Noel Gallagher and Oasis for plagiarism on three occasions. The first was the case of Neil Innes (formerly of the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band and the Rutles) suing to prove the Oasis song "Whatever" borrowed from his song "How Sweet to Be an Idiot". Innes was eventually awarded royalties and a co-writer credit.[178] Noel Gallagher said in 2010 that the plagiarism was unintentional and he was unaware of the similarities until informed of Innes's legal case.[179] In the second incident, Oasis were sued by Coca-Cola and forced to pay $500,000 in damages to the New Seekers after it was alleged that the Oasis song "Shakermaker" had lifted words and melody from "I'd Like to Teach the World to Sing".[178] When asked about the incident, Noel Gallagher joked "Now we all drink Pepsi."[180] On the third and final occasion, when promotional copies of (What's the Story) Morning Glory? were originally distributed, they contained a previously unreleased bonus song called "Step Out". This promotional CD was quickly withdrawn and replaced with a version that omitted the controversial song, which was allegedly similar to the Stevie Wonder song "Uptight (Everything's Alright)". Official releases of "Step Out", as the B-side to "Don't Look Back in Anger" and on Familiar to Millions, listed "Wonder, et al." as co-writers.[181]

The 2003 song "Life Got Cold" by UK band Girls Aloud received attention due to similarities between the guitar riff and melody of the song and that of the Oasis song "Wonderwall".[182][183] A BBC review stated "part of the chorus sounds like it is going to turn into 'Wonderwall' by Oasis."[184] Warner/Chappell Music has since credited Noel Gallagher as co-songwriter.[185]

Legacy and influence

[edit]Despite parting ways in 2009, Oasis remained influential in British music and culture and are recognised as one of the biggest and most acclaimed bands of the 1990s.[citation needed] They are recognized as one of the spearheads of Britpop, which has claimed a prominent place in British music.[citation needed] With their record breaking[citation needed] sales, concerts, sibling disputes, and their high-profile chart battle with Britpop rivals Blur, Oasis were a major part of 1990s UK pop culture, an era dubbed Cool Britannia.[citation needed] Many bands and artists have cited Oasis as an influence or inspiration, including Arctic Monkeys,[186] Catfish and the Bottlemen,[187] Deafheaven,[188] the Killers,[189] Alvvays,[190] Maroon 5,[191] Coldplay,[192] and Ryan Adams.[193]

The band's success also helped local businesses. Pete Caban, owner of Bandwagon Music Supplies in Perth, Scotland, which closed in 2020 after 37 years in business, said: "The highlight years were the mid-90s to the early 2000s. That was the peak period. The Oasis period, as I call it, where everyone wanted to buy a guitar. That was the game changer for music and for me here in Perth. I was shovelling guitars out the door at the point. So hurrah for Noel Gallagher."[194]

In 2007, Oasis were one of the four featured artists in the seventh episode of the BBC/VH1 series Seven Ages of Rock – an episode about British indie rock – along with Britpop peers Blur in addition to the Smiths and the Stone Roses.[195]

In 2023, an unofficial music project by the name of AISIS was the first full-length album to use AI vocals. The project attracted more than half a million views within six weeks of publication, including newspaper articles written about it,[citation needed] and brought Breezer, the band that created the project, out of obscurity and landed them live dates.[196] Bobby Geraghty and his Breezer bandmates wrote original Oasis-style songs and then used AI to create audio deepfakes based on Liam Gallagher's voice alongside their original instrumentation. Liam himself approved of the album, saying that he "sounded mega".[197]

Oasis received a nomination for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on their sixth year of eligibility in February 2024. Initially, the members included in the nomination were the Gallagher brothers, McGuigan, White, Arthurs, McCarroll, Archer, and Bell. Liam Gallagher feels that the organization is not authentic when it comes to rock music.[198][199]

Band members

[edit]Current members

[edit]- Liam Gallagher – vocals, tambourine (1991–2009, 2024–present); acoustic guitar (2001–2002, 2007–2008)

- Noel Gallagher – lead guitar, vocals (1991–2009, 2024–present); rhythm guitar (1991, 1999–2009, 2024–present); keyboards (1993–2009); bass (1993–1994, 1995, 1999)

Former members

[edit]- Paul "Bonehead" Arthurs – rhythm guitar (1991–1999); lead guitar (1991); keyboards (1994–1997); bass (1995)

- Paul "Guigsy" McGuigan – bass (1991–1995, 1995–1999)

- Tony McCarroll – drums (1991–1995)

- Alan "Whitey" White – drums, percussion (1995–2004)

- Gem Archer – rhythm and lead guitar (1999–2009); backing vocals (2002–2003); keyboards (2002–2005); harmonica (2005–2009)

- Andy Bell – bass (1999–2009); rhythm guitar (2003–2009); keyboards (2007–2009)

Former touring members

[edit]- Scott McLeod – bass (1995)

- Mike Rowe – keyboards (1997–2000, 2001)

- Matt Deighton – rhythm guitar (2000)

- Zeb Jameson – keyboards (2000–2001)

- Steve White – drums, percussion (2001)

- Jay Darlington – keyboards (2002–2009)

- Zak Starkey – drums, percussion (2004–2008)

- Chris Sharrock – drums, percussion (2008–2009)

Timeline

[edit]

Touring timeline

[edit]

Discography

[edit]- Definitely Maybe (1994)

- (What's the Story) Morning Glory? (1995)

- Be Here Now (1997)

- Standing on the Shoulder of Giants (2000)

- Heathen Chemistry (2002)

- Don't Believe the Truth (2005)

- Dig Out Your Soul (2008)

Concert tours

[edit]- Definitely Maybe Tour (1994–1995)

- (What's the Story) Morning Glory? Tour (1995–1996)

- Be Here Now Tour (1997–1998)

- Standing on the Shoulder of Giants Tour (1999–2001)

- The Tour of Brotherly Love (2001)

- 10 Years of Noise and Confusion Tour (2001)

- Heathen Chemistry Tour (2002–2003)

- Don't Believe the Truth Tour (2005–2006)

- Dig Out Your Soul Tour (2008–2009)

- Oasis Live '25 Tour (2025)

Awards and nominations

[edit]- Brit Awards: 6 wins from 18 nominations, including Outstanding Contribution to Music and Best Album of the Last 30 Years for "(What's the Story) Morning Glory?".[1]

- Grammy Awards: 2 nominations, including Best Rock Vocal Performance by a Duo or Group and Best Rock Song.[3]

- NME Awards: 17 wins from 26 nominations.[4]

- Q Awards: 9 wins from 19 nominations.[5]

- MTV Europe Music Awards: 4 wins from 4 nominations.

- Ivor Novello Awards: 2 wins from 3 nominations.

Oasis has also been recognized by other award bodies, such as the MTV Japan Awards, UK Video Music Awards, and the Mercury Prize.[200]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b Stegall, Tim (23 July 2021). "10 reasons why Oasis are the most influential Britpop band of all time". Alternative Press. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ "Oasis reunion live: Tickets officially sold out - as fans complain about surge in prices". Sky News. 31 August 2024. Retrieved 31 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Some might say Oasis are still world beaters after Slane gig". The Belfast Telegraph. 22 June 2009. Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ a b "Noel Gallagher says "no point" in Oasis reforming as band sells "as many records now" than when together". NME. 18 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Oasis, Coldplay & Take That enter Guinness World Records 2010 Book – Guinness World Records Blog post". Community.guinnessworldrecords.com. Archived from the original on 24 January 2010. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ^ "Oasis receive Outstanding Brit Award". NME. 19 October 2006. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "The Official Oasis Website | Oasis Be Here Now reissue". Oasis. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- ^ “GRAMMY Award Results for Oasis” Archived 16 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine. National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 9 September 2019

- ^ Harris, John. Britpop!: Cool Britannia and the Spectacular Demise of English Rock. Da Capo Press, 2004. ISBN 0-306-81367-X, pg. 124–25

- ^ "Oasis, Other – The Boardwalk, 14 August 1991 – Manchester Digital Music Archive". Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Oasis' setlist at their first-ever gig with Noel Gallagher". 19 October 2020. Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ McCarroll, Tony (2011). "Chapter 3: A Definite Maybe". Oasis The Truth. John Blake.

- ^ Harris, pg. 125–26

- ^ Harris, pg. 127–28

- ^ VH1 Behind the Music, VH1, 2000

- ^ Dingwall, John (17 November 2013). "Music guru Alan McGee: If I'm being honest.. all I could wish for came true". Daily Record. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ "Oasis." Encyclopedia of Popular Music, 4th ed. Ed. Colin Larkin. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Harris, pg. 131

- ^ Harris, pg. 149

- ^ Mundy, Chris (2 May 1996). "Ruling Asses: Oasis Have Conquered America, and They Won't Shut Up About It". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ Harris, pg. 178

- ^ Grundy, Gareth (30 August 2009). "Born To Feud". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Harris, pg. 189

- ^ Harris, pg. 213

- ^ "Supanet entertainment music feature". Supanet.com. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "£550,000 for sacked Oasis drummer". BBC News. 3 March 1999. Archived from the original on 30 June 2003. Retrieved 3 February 2008.

- ^ a b Harris, pg. 226

- ^ "When Blur beat Oasis in the battle of Britpop". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ Harris, pg. 235

- ^ Harris, pg. 233

- ^ Author unknown. "Cockney revels". NME. 26 August 1995.

- ^ "Noel Gallagher in Blur Aids outburst". Melody Maker. 23 September 1995.

- ^ Harris, pg. 251

- ^ Robinson, John (19 June 2004). "Not here now". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ Copsey, Rob (4 July 2016). "The UK's 60 official biggest selling albums of all time revealed". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ^ "Queen head all-time sales chart". BBC News. 16 November 2006. Archived from the original on 4 February 2007. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ Mason, Tom; Randall, Lucian (2012). Noel Gallagher - The Biography. John Blake. ISBN 9781782190912.

- ^ Alan McGee (2013) "Creation Stories: Riots, Raves and Running a Label". p. 31. Pan Macmillan,

- ^ Harris, pg. 298–99

- ^ Live Forever: The Rise and Fall of Brit Pop (DVD). London: Passion Pictures. 2004.

- ^ Strauss, Neil (10 September 1996). "Sounding Like the Beatles, And Acting More Popular". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ Haydon, John. "The List: Liam Gallagher's worst moments". The Washington Times. Archived from the original on 4 August 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Harris, pg. 310

- ^ a b "1996 MTV Video Music Awards". MTV. Archived from the original on 12 June 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Harris, pg. 312

- ^ Harris, pg. 313

- ^ a b c d e f "'Flattened by the cocaine panzers' – the toxic legacy of Oasis's Be Here Now". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ Harris, pg. 342.

- ^ "Rolling Stone news article". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 15 July 2007. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "Noel Gallagher has a lot of regrets about 'Be Here Now'". NME. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Wave Magazine News article. Retrieved 9 March 2008. Archived 16 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Gallagher shrugs off Oasis departure". BBC News. 10 August 1999. Archived from the original on 12 November 2005. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ St. Michael, Mick (1996). Oasis: In Their Own Words. Omnibus Pr. ISBN 0-7119-5695-2.

- ^ "Gallagher brothers say oasis bassists departure wont kill the band". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 18 January 2008. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "tripod.com". Mad4gem.tripod.com. Archived from the original on 30 July 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Randall, Lucian (2012). Noel Gallagher – The Biography. Kings Road Publishing.

- ^ Oasis – Official Website – Discography retrieved on 15 December 2007. Archived 11 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Billboard.com – Discography – Oasis – Standing on the Shoulders of Giants[dead link] retrieved on 15 December 2007

- ^ "Top 40 Singles". Thetop40charts.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ a b Standing on the Shoulders of Giants > Overview . Written by Stephen Thomas Erlewine. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ Boehlert, Eric. "My, how the Giants Have Fallen: Oasis, Pumpkins Suffer Huge Sales Slides In Second Week". Archived 27 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Rolling Stone. 15 March 2000.

- ^ "Oasis Noel quits tour". BBC News. 23 May 2000. Archived from the original on 1 September 2009. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- ^ Familiar to Millions > Overview. Written by Stephen Thomas Erlewine. Retrieved 15 December 2007

- ^ "Elvis and Oasis enjoy chart success". BBC News. 7 July 2002. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- ^ Heathen Chemistry > Charts & Awards > Billboard Albums. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- ^ a b Heathen Chemistry > Overview. Written by Stephen Thomas Erlewine. Retrieved 14 December 2007.

- ^ [1] Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Brawling Oasis singer 'on drugs'". BBC News. 5 May 2004. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ "Oasis singer could face jail for bar brawl". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Independent News article Archived 17 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ Pill, Steve (18 October 2004). "Death in Vegas". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ M, Staff (15 January 2015). "Noel Gallagher talks about past collaborations with Amorphous Androgynous and Death In Vegas". OasisMania. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ "Alan White". Oasis Official Website. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ "ALAN WHITE'S DEPARTURE FROM OASIS CONFIRMED". NME. 16 January 2004. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ "Steve White | Drummer | Percussionist | Educator | The Official Site". Whiteydrums.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2015.

- ^ "NME news article". NME. 12 September 2005. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ Bishop, Tom (26 June 2004). "Oasis fail to surprise Glastonbury". BBC News. Archived from the original on 28 May 2006. Retrieved 3 February 2008.

- ^ "Zak Starkey fan site". Kathyszaksite.com. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "NME news article". NME. 12 September 2005. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "Telegraph news article". Archived from the original on 25 October 2007. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "Oasis Chart history" Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Official Charts Company. Retrieved 1 December 2014

- ^ "Oasis: Don't Believe the Truth" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ McLean, Craig (4 June 2005). "Back in anger (...continued)". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- ^ "Oasis announce details of 'Lord Don't Slow Me Down' DVD". Uncut. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ "Chart Attack – Best Magazine 2021". Chart Attack. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011.

- ^ "Oasis 'Outstanding' at BRIT Awards". NME. 14 February 2007. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "NME News article". NME. 24 September 2007. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "Rocklist.net...Q Magazine Lists". Rocklistmusic.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ Oasis Net news article. Retrieved 9 March 2008. Archived 9 December 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Oasis tour dates". Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ a b Thompson, Robert. "Noel Gallagher Describes on-Stage Attack" Archived 24 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine. billboard.com. 24 March 2010.

- ^ "The Oasis Newsroom". Live4ever.us. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ Jonze, Tim (26 February 2009). "Oasis win best British band at NME awards". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ^ "Oasis, Alex Turner, Killers: Shockwaves NME Awards 2009 nominations | News". NME. 26 January 2009. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ "Oasis Refund £1 million – Souvenir Checks Worth Selling". idiomag. 21 July 2009. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ^ "Oasis Wembley Stadium Sound Blip". idiomag. 10 July 2009. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ "Oasis cancel V festival Chelmsford headline slot". NME. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ "Hangovers, guitar attacks and flying plums: the real reasons Oasis split". The Independent. 23 September 2015. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ "Liam Gallagher sues brother Noel Gallagher for libel". BBC News. 19 August 2011. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ "Liam Gallagher drops lawsuit against Noel Gallagher – NME". NME. 24 August 2011. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ "Oasis annule son concert à Rock-en-Seine et se sépare". Le Parisien. France. 29 August 2009. Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ "Oasis annonce la fin du groupe rock". Ouest France. 29 August 2009. Archived from the original on 9 January 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ^ "A statement from Noel". 28 August 2009. Archived from the original on 29 August 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- ^ "Music – News – Oasis split as Noel Gallagher quits band". Digital Spy. 28 August 2009. Archived from the original on 3 November 2009. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ "Noel Gallagher Quits Oasis after Paris altercation" Archived 16 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. NME. Retrieved 22 June 2015

- ^ "Oasis – Liam Gallagher renames Oasis". Contactmusic.com. 5 February 2010. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ "Ride Reunite, Announce World Tour". Pitchfork. 18 November 2014. Archived from the original on 11 April 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Harper, Kate (16 February 2010). "Oasis Album Declared Best of Past 30 Years at BRIT Awards". Chart Attack. Archived from the original on 25 April 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "Liam Gallagher snubs Noel as Oasis win Brit Album of 30 Years award". NME. 16 February 2010. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Hudson, Alex (15 March 2010). "Liam Gallagher Explains Noel Snub at Brit Awards". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on 1 December 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ "Time Flies for Oasis | Music | STV Entertainment". Entertainment.stv.tv. 1 April 2010. Archived from the original on 10 April 2010. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100 (20 June 2010 – 26 June 2010)". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Dombal, Ryan (22 May 2014). "Oasis – Definitely Maybe: Chasing the Sun Edition". Pitchfork Media. Archived from the original on 23 May 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ "'Supersonic' has been revealed as new Oasis documentary title". NME. 15 May 2016. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2016., 'Supersonic' has been revealed as a new Oasis documentary title. Retrieved 16 May 2016

- ^ Lewis, Isobel (14 July 2021). "Oasis Knebworth 1996: Liam and Noel Gallagher announce release date of documentary film". The Independent. Archived from the original on 10 August 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (29 April 2020). "Noel Gallagher announces release of lost Oasis song". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 100 (8 May 2020 – 14 May 2020)" Archived 3 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Official Charts Company. Retrieved 23 July 2020

- ^ a b Mather, Victor (27 August 2024). "Oasis: Timeline of a Sibling Rivalry for the Ages". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ a b Brandle, Lars (27 August 2024). "Oasis Is Reuniting For 2025 Tour". Billboard. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Whitehead, Jamie (27 August 2024). "Oasis confirm reunion with 2025 world tour announced". BBC. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Johnson, Brooke Ivey (28 August 2024). "Original Oasis member 'confirmed' to return for 2025 reunion tour". Metro. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Johns, Victoria (28 August 2024). "Paul 'Bonehead' Arthurs takes stance on Gallagher brothers feud as Oasis reunite". The Mirror. Retrieved 28 August 2024.

- ^ Jones, Damian (2 September 2024). "Gem Archer is "looking very likely" to join Oasis line-up for their 2025 reunion tour". NME. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ Jefferies, Mark (4 September 2024). "Liam and Noel Gallagher pick latest ex band member they want on Oasis tour". The Mirror. Retrieved 5 September 2024.

- ^ a b "Oasis line-up: Noel and Liam reportedly look to son of Beatles star as three musicians are 'confirmed' | Virgin Radio UK". virginradio.co.uk. 9 September 2024. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ "Oasis reunion: Alan White teases joining line-up for 2025 tour". Radio X. 2 September 2024. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ "Original Oasis drummer Tony McCarroll reacts to reunion & whether he'll be asked back: "I'm not holding my breath"". Radio X. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ Dunworth, Liberty (19 September 2024). "Liam Gallagher says "there could be a few new faces" in Oasis reunion tour band". NME. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100 | Official Charts". www.officialcharts.com. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 40 | Official Charts". www.officialcharts.com. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ https://www.nme.com/news/music/liam-gallagher-teases-that-hes-blown-away-by-music-noel-has-written-for-new-oasis-album-3809373

- ^ https://www.nme.com/news/music/is-liam-gallagher-teasing-us-with-a-new-oasis-album-its-already-finished-3791619

- ^ Jones, Damian (4 November 2024). "Liam Gallagher teases that he's "blown away" by music Noel has written for new Oasis album". NME. Retrieved 6 November 2024.

- ^ Corcoran, Nina (30 September 2024). "Oasis Add North American Dates to 2025 Reunion Tour". Pitchfork. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ Strauss, Matthew (5 November 2024). "Oasis Extends 2025 Reunion Tour Into South America". Pitchfork. Retrieved 8 November 2024.

- ^ Skinner, Tom (7 October 2024). "Oasis announce Australian dates of Live '25 reunion tour". NME. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ a b "Classic Reviews: Oasis '(What's the Story) Morning Glory' and Blur's 'The Great Escape'". Spin. 2 October 2015. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ Faulk, Barry J. (2016). British Rock Modernism, 1967–1977: The Story of Music Hall in Rock. Routledge. p. 19. ISBN 9781315570273.

- ^ Kenny, Glenn (25 October 2016). "Review: In 'Supersonic,' the Band Oasis and Its Combative Brothers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ Stegall, Tim (23 July 2021). "10 Reasons Why Oasis Are The Most Influential Britpop Band Of All Time". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on 26 July 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ Brennan, Steve (16 April 2014). "20 Greatest Britpop Bands of All Time". New Times Broward-Palm Beach. p. 6. Archived from the original on 14 November 2021. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ O'Brien, Jon (27 August 2024). "10 Ways Oasis' 'Definitely Maybe' Shaped The Sound Of '90s Rock". Grammy.com. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ O'Brien, Jon (27 August 2024). "Part 8: 1997: The ballad of Oasis and Radiohead". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Hale, Clint (10 August 2017). "Rock Is a Lot Duller With Oasis Out of the Picture". Houston Press. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ a b Mapes, Jillian (27 May 2014). "Oasis vs. Shoegaze vs. Grunge: An Excerpt From Alex Niven's 33 1/3 Book 'Definitely Maybe'". Flavorwire. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Flick, Larry (6 March 1999). "Continental Drift: Unsigned Artists And Regional News". Billboard. Vol. 111, no. 10. p. 22. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 14 November 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Song of the Year 1995: Oasis Wonderwall". The Times. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- ^ "Can Coldplay steal Oasis's crown?". The Telegraph. London. 12 May 2005. Archived from the original on 23 May 2005. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ "The Beatles' musical footprints". BBC News. 30 November 2001. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- ^ Coffman, Tim (8 January 2024). "The Oasis song Noel Gallagher thought was better than John Lennon". Far Out Magazine. Retrieved 25 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Noel Gallagher & Bonehead". Hotpress. 6 September 1994.

- ^ "How Live Forever became Liam Gallagher's favourite Oasis song". Radio X. 8 August 2024. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ Kielty, Martin (8 June 2023). "How Noel Gallagher Blatantly Stole Pete Townshend's Guitar Sound". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ Childers, Chad (29 September 2023). "Noel Gallagher calls Oaisis' "Definitely Maybe" the "Last Great Punk Album"". Loudwire. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ "Noel Gallagher - interview". Guitar World. April 2000.

- ^ Starkey, Arun (3 May 2021). "How Paul Weller inspired Noel Gallagher to pick up a mysterious guitar". Far Out Magazine. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ "Noel's guitar army! - Noel Gallagher interview". 2000.

- ^ a b c d "Noel & Liam Gallagher". NME. 2 April 1994.

- ^ "Noel Gallagher Interview". San Francisco Chronicle. 25 January 1998.

- ^ "Gallagher Admits Bee Gees Debt". Contactmusic.com. 29 November 2006. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ Peplow, Gemma (2 September 2022). "Noel Gallagher reveals how 'all-time great' David Bowie inspired him to 'put himself out there'". Sky News. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Bosso, Joe (19 August 2008). "Noel Gallagher says new Oasis album isn't 'Britpop'". MusicRadar. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Oasis' Noel Gallagher reveals his Top 10 bands". NME. 3 September 2008. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ Curran, Shaun (17 March 2021). "The mystery of 'lost' rock genius Lee Mavers". BBC. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ "Noel Gallagher – Interview". Addicted to Noise. 1 February 1995.

- ^ "Noel Gallagher Interview". Q Magazine. 1 February 1999.

- ^ Taysom, Joe (9 November 2021). "Noel Gallagher's favourite Pink Floyd album". Far Out Magazine. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ Drew, Mark (21 October 2017). "Noel Gallagher: Oasis would never have formed if it wasn't for Slade". Express and Star. Retrieved 21 September 2024.

- ^ "Noel Gallagher on The Smiths". Archived from the original on 22 March 2007. Retrieved 7 February 2011 – via YouTube.

- ^ Doran, John (17 October 2011). "Noel Gallagher Selects His Thirteen Favourite Albums". The Quietus. Retrieved 20 September 2024.

- ^ "Noel Gallagher about Stone Roses". 8 October 2009. Archived from the original on 22 August 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2011 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Noel Gallagher – interview". NME. 16 February 2002.

- ^ "Original Oasis about stealing from other musicians". 25 October 2009. Archived from the original on 24 May 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2011 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Noel Gallagher Interview". Uncut. 1 March 2000.

- ^ Thomas, Stephen. "Oasis". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 17 October 2010. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ "Twenty-five years of Oasis, the best British band of their generation". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ Grundy, Gareth (30 August 2009). "Born to feud: how years of animosity finally split Oasis boys". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ a b Sean Michaels (6 October 2008). "Have Oasis plagiarised Cliff Richard?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ "Whatever – 'Time Flies...1994–2009' Clip". 19 May 2010. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2011 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Oasis | Rolling Stone Music". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ Rabid, Jack. "Don't Look Back in Anger". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ "Blu secure at number one in midweeks". CBBC Newsround. BBC. 20 August 2003. Archived from the original on 5 May 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ^ "Girls Aloud – Life Got Cold". Tourdates.co.uk. 18 August 2003. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- ^ Youngs, Ian (23 May 2003). "Girls Aloud trounce pop rivals". BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2008.

- ^ "Life Got Cold". Warner/Chappell Music. Warner Music Group. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ "Arctic Monkeys' Alex Turner: 'We used to pretend to be Oasis in school assembly'". NME. 12 May 2012. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ Perry, Kevin (14 March 2015). "Catfish And The Bottlemen Interview". NME. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- ^ "Deafheaven on Trying to Top 'Sunbather' and Prove Their Metal". Rolling Stone. 25 August 2015. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

"Ordinary Corrupt Human Love Is Deafheaven's Masterwork". vinylmeplease.com. 9 July 2018. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2018. - ^ Grow, Kory (29 September 2018). "The Killers: How We Wrote 'Mr. Brightside'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Bartleet, Larry (7 September 2017). "Alvvays interview: Molly Rankin on Oasis, MGMT, 'Antisocialites'". NME. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

"Alvvays". Pitchfork. 23 February 2015. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019. - ^ Patterson, Sylvia (25 August 2007). "Maroon 5: They will be loved". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "Chris Martin speaks of love for Oasis' (What's The Story) Morning Glory". gigwise.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Andrew Trendell, "Ryan Adams on the 'genius' of Oasis: 'They're like Star Wars'" Archived 8 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, NME, 9 December 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Perth music shop to shut after four decades as owner blames years of delayed works at city centre landmark" Archived 28 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine – The Courier, 4 August 2020

- ^ "Seven Ages of Rock". BBC. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ "'We got bored waiting for Oasis to re-form': AIsis, the band fronted by an AI Liam Gallagher | Oasis | The Guardian". amp.theguardian.com. 18 April 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ Reilly, Nick (19 April 2023). "Liam Gallagher responds to AI Oasis album: 'I sound mega!'". Rolling Stone UK. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ Legaspi, Althea (12 February 2024). "Liam Gallagher Slams Rock Hall of Fame After Oasis Nomination: 'There's Something Very Fishy About Those Awards'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "Oasis Biography". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved 10 February 2024.

- ^ SMF (23 March 2021). "Oasis". Song Meanings and Facts. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Cohen, Jason (18 May 1995). "The Trouble Boys – Cross the Atlantic with a Hot Record, Two Battling Brothers and Attitude to Spare". Rolling Stone. pp. 50–52, 104.

- Harris, John. Britpop!: Cool Britannia and the Spectacular Demise of English Rock. Da Capo Press, 2004. ISBN 0-306-81367-X.

- Mundy, Chris (2 May 1996). "Oasis: Ruling Asses". Rolling Stone. pp. 32–35, 68.

External links

[edit]- Oasis (band)

- 1991 establishments in England

- 2009 disestablishments in England

- 2024 establishments in England

- Brit Award winners

- MTV Europe Music Award winners

- Britpop groups

- Creation Records artists

- Columbia Records artists

- Epic Records artists

- English musical quintets

- English rock music groups

- English alternative rock groups

- Ivor Novello Award winners

- Musical groups established in 1991

- Musical groups disestablished in 2009

- Musical groups reestablished in 2024

- NME Awards winners

- Reprise Records artists

- Rock music groups from Manchester

- Sibling musical groups

- Sony Music UK artists